“If Sanskrit is made by the gods, is Marathi made by thieves? … How can Hindi be India’s national language when its native speakers are not as numerous as we thought?”

It was the summer of 2024, I had read two interesting articles mentioning "India: A Linguistic Civilization" by Ganesh Narayandas Devy. He is an acclaimed language activist and the mastermind behind the People’s Language Survey of India (PLSI), a comprehensive documentation of all the living languages spoken by the people of India, the largest-ever survey of languages in history. I grew interested and ordered a copy the following day.

"India: A Linguistic Civilization" is a retelling of the history of the subcontinent through the eyes of a linguist, it is an all-encompassing book that seeks to uncover our rich linguistic history and showcases the various events that shaped India into the beautiful linguistic blend it stands as today, and also serves as a cautionary tale of the horrors that lie ahead which threaten its sanctity.

The oral language period

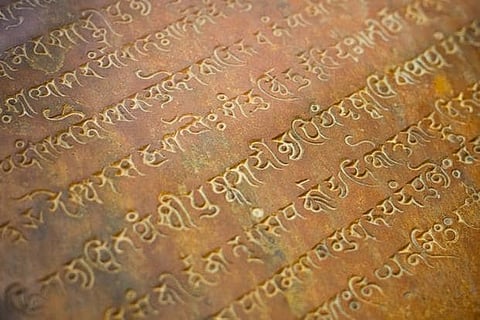

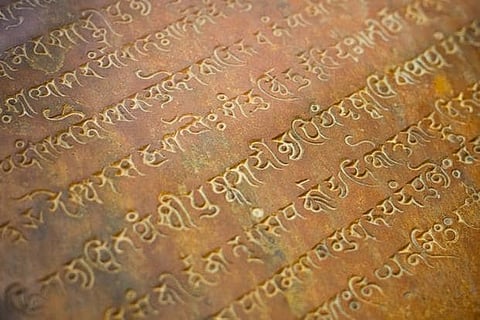

The book begins by describing India’s past. Prior to the advent of writing, India had one of the most detailed oral traditions. Sagas of information were orally passed down over the generations. This knowledge was known as smriti and it was the heart of the oral tradition. What is important to note here is that rather than simple pieces of information, these oral traditions were entire knowledge systems, an integral part of their people’s identities.

As Devy writes “What do these languages hold in them? They hold knowledge about ecology. I was compiling a list of Himalayan languages in three states - Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, and Uttarakhand — and found that there are numerous terms for snow. They have a word for snow which falls on muddy waters, snow which falls in the latter part of the afternoon, the first and last phase of snow and so on. All these indicate great knowledge of ecology in these days when we are all worried about climate change and global warming. We are losing or we are bound to lose such information.”

Before the arrival of Sanskrit, the ancestor of the Dravidian languages of the South, Proto-Dravidian, existed in some parts of India. Later on, when the Indo-Aryans spread throughout India, their languages also diversified.

Subsequently, the various tongues of India came along, with the earliest form of our Kashmiri tongue developing around the 13th century from a dialect of the Indo-Aryan language.

The book delves into ideas hitherto unthought of in the context of linguistics, such as the role of caste, paying homage to the great Dr B R Ambedkar and his work on the history of the caste in the process.

Written and literary period

The next chapter of India’s history, the era of the British Raj, is presented under the context of literary traditions. The Indian people, now creating literature while also keeping their oral tradition alive, live in a state of harmony. The Bhakti movement strengthened oral traditions enough to keep them alive, while Sanskrit literature faced a decline in favour of Bhakti poetry and Indigenous literature, which saw an emergence that coincided with the era of Islamic rule.

The supramundane, almost mystical power of script is mentioned. The advent of Turkish paper merchants, according to Devy, marks a point in history when skills such as good penmanship became both admired and highly valued. All of this information is presented whilst also recalling two great stories, one of how Vyasa, with Ganesha as his scribe, wrote the Mahabharata using his tusk and one of the renowned poet Ghalib’s writings getting lost.

However, after the British arrived in India, new norms of literary tradition were introduced, which favoured written works and diminished the power of oral tradition. A set of biases emerged, making those languages with only oral traditions become inferior to ones with writing systems, thus creating a disparity that continues to this day in a much more different form, the schedule of languages.

Furthermore, the book explains how the concept of linguistic states; a flawed concept invented for ease of governance which Nehru cautioned against, caused the partition of Bengal in 1905 and subsequently started the slippery slope that is state reorganisation that continues to this day.

The Modern language period

The narrative shifts towards a question that resonated deeply with me, that is, why do people turn to English for their economic betterment?

This question seems to have a deceptively simple answer: globalization. But on the contrary, the real problems with this answer seem to lie closer to home. Once again, let’s look at the British era, during which certain languages were chosen for publication and this action led to multiple changes in our nation’s status quo.

After English and Hindi, Bengali, Punjabi and Marathi are the next major literary languages. These languages are, according to Devy, ‘safe’ for the most part. The orally transmitted languages are the ones at risk since in a scenario where a language entirely lacks publication, it becomes forgotten and dies out, thus leaving no trace of the knowledge system that existed with it. This harrowing reality is one we are somehow content with. We are apparently ready to abandon our own language, a part of our culture, our identity, in the name of a better future, ultimately leaving our roots behind.

Language holds a certain gravitas over the public. The argument can be made that language is the tool that all leaders must harness to their advantage.

The author then talks about the post-independence era, which produced one of the most daunting issues of our time; the ubiquitous use of Hindi.

Originally thought of as a replacement for English, a provision was kept that it would be entirely phased out after 1965. However, this was clearly a tall order, a potentially destructive one as well, Devy remarks, citing the fate of Germany and Italy following their decision to opt for unilingual nations during the 20th century. Eventually, a more flexible solution had to be constructed, one that allowed English and Hindi to coexist.

Devy seemingly has a gripe with the government’s attitude towards language. He asks, ”How can Hindi be India’s national language when its native speakers are not as numerous as we thought?”

This question is a jab at the government’s style of survey taking. Hindi, as we know it, only has 38 crore speakers. The government, however, increases the numbers by adding in the speakers of languages which are mutually unintelligible with Hindi to begin with. This distends the number to a barely admissible 121 crores, a far cry from the original numbers.

This temerity, as he describes it, forms a kind of hegemony that prevails in India that indirectly kills free thinking and as a result, leads to language loss. Here, he likens language loss to genocide.

The print technology era

This part of the book begins with what can only be described as the most discussed part of the book. Here, Devy raises a question of “language fatigue” as he calls it.

He states that languages are seemingly becoming redundant and a new, more efficient style of communication will soon emerge, likely based on images. Broca’s lobe, the area of the brain largely responsible for language, is showing ‘great fatigue’. As a result, children no longer want to read or write.

He marks this transitional era as an important turning point in our evolutionary history, one with lasting impact on our future. Ultimately, in the path towards further evolution, humans may actually abandon language and its constraints in favour of newer ways of “thinking”.

Another matter of concern he highlights is the fact that the need for memory has decreased drastically with the advent of digitization. In an era where information is so frequently blazoned digitally, making us increasingly tedious. The repercussions of such a change are clearly visible, with the ever-shortening attention span of the average Joe.

Returning to the topic of linguistic globalization, he highlights Artificial Intelligence (AI) as a major threat to the world’s language diversity. Not only will it be the catalyst for the linguistic genocide, he imagines, but also an unknowable number of knowledge systems, both arcane and contemporary, will go down with it. Migration, loss of identity, segregation and alienation will also occur at the hands of this globalization.

Tribes are certainly the ones threatened the most. So, he underscores the usage of techniques such as documentation of languages and the publishing of stories in order to curb marginalization.

As the book nears its conclusion, the book draws on the familiar preachings of Dr B R Ambedkar, which are brought up in the context of this marginalization. The concept of caste discrimination, according to him, is why Indian knowledge production faced so many hindrances. This one quote is enough to help condense the entire premise of the book into a tale of disparities.

Between literature and folk literature, between languages and dialects, between the oral tongues and ‘written’ tongues, and between traditional knowledge (the smriti passed through apprenticeship) and canonized knowledge.

I highly recommend this book to those who would like a new perspective when it comes to the history of our country.

Muhammad Awan is a student of 9th standard. He can be reached at: mohammadawan449@gmail.com, @muhammadawan7 (You Tube)

Have you liked the news article?