Storytelling from the heartlands of our country is extremely complex. The narratives have shades of grey and defy the simplistic evil vs virtuous stands.

There are Waghoba shrines in forest areas dedicated to tigers/leopards that are worshipped by the local communities; there are also festivals, like the Sikari Utsav, which celebrate hunting.

My first encounter with this paradox was 20 years ago, in 2005, at the Melghat Tiger Reserve in the Vidarbha region of Maharashtra. It was when the Ministry of Environment and Forests (Project Tiger) had set up a task force to review the management of tiger reserves in the country.

Battlelines had been forcibly drawn between the big cat and the local forest communities that were being displaced for the conservation of the tiger. Sunita Narain, director general of New Delhi-based Centre for Science and Environment (CSE), was the chairperson of the task force. She was also my editor at the Down To Earth magazine where I was a reporter.

The situation was tense at Melghat where I visited several villages bordering the core area and within the buffer zone of the tiger reserve. Churni, Pastalai, and Vairath villages were slated for an immediate relocation and rehabilitation.

The Gawli community, traditionally cattle rearers and milk supplies inhabited Churni and Vairath, and it was the Korku tribe that lived in Pastalia; most of them practised subsistence farming.

These communities claimed they had lived in the forest lands alongside wild animals for generations. The cattle belonging to the Gawlis grazed in the jungle. The villagers were being evicted from the forests to save the tiger, whom they worshipped as waghoba.

“Till now we used to live with the bagh [tiger] and did not disturb it. But now if I see a bagh, I will shoot it down because it is forcing us to turn homeless,” an elderly member of the Gawli community from Vairath told me.

The government had made alternative arrangements for these villagers but most were unhappy with the rehabilitation package and the ‘poor’ quality of land that was allotted to them. Villagers of Vairath were allotted land in a river!

I remember struggling to write that report. It was a complex situation. Should one ‘side’ with the government and conservationists who wanted the forest-dwelling communities out of the forest to protect a flagship species. Or, should it be about the rights of the Adivasis and forest dwelling communities who have lived there for generations and have known no other home? Their lives and livelihoods directly depended on the forests.

My editor Narain, sensing my conflict, advised me, “Just write what you found out and what the villagers and forest officials told you. Conservation in our country is a complex matter and there are no easy answers and simple solutions.”

These words have stayed with me and guided me as I tread the path of an environmental journalist. Every new story that I have reported on, has presented another complex facet of conservation in the country.

One of them is about the hunting festival in West Bengal held during the dry season (March-May) in the districts of Jhargram, Paschim Medinipur, Bankura, Purulia, and Birbhum.

As part of this annual hunting festival, thousands of men and boys, armed with bows, arrows and catapults, enter the forests to hunt wild boars and wild hares.

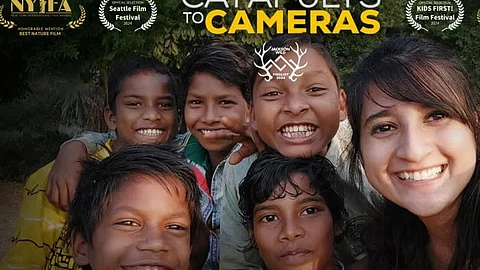

In her film Catapults to Cameras, a 40-minute film produced by RoundGlass Sustain, director Ashwika Kapur, a Kolkata-born wildlife filmmaker says, “It is an unnerving sight. Villagers return from the forest carrying hoards of dead wild animals and birds. Anything they find moving or crawling in the forest, they kill it. It is gory and shocking because such hunting is banned.”

Catapults to Cameras was recently screened at the National Centre for Performing Arts (NCPA), Mumbai. Post screening, the filmmaker joined the audience virtually for an interactive session. RoundGlass Sustain is a not-for-profit initiative that tells stories of India's natural world to document science, create awareness, and support conservation.

Kapur said that the film sets out on a deeply personal quest to uncover the roots of an illegal wildlife hunting festival in the forests of her home state, West Bengal. She described the annual hunting festival as an illegal blood sport, where thousands of protected animals are massacred.

WATCH 'Catapults to Cameras'

Kapur found that children as young as three years old were “handed catapults as weapons in an assault against wildlife”.

Deeply disturbed by what she witnessed, she teamed up with conservationist Suvrajyoti Chatterjee “to inspire change where it matters most — in the hearts of children within these hunting communities. ”

And that is what the film Catapults to Cameras is all about. Kapur gave cameras to five children from the hunting community as an experiment, and that became a film.

The five boys — Raja, Ajoy, Tarash, Surajit and Lalu — routinely killed birds with their catapults. Kapur wanted to know if they traded their catapults for cameras, anything would change in the way the five boys viewed wildlife, when they saw it through a camera lens.

Cameras in hand the boys travelled with Kapur and Chatterjee. They ‘shot’ wildlife with their cameras. There are poignant moments in the film when kids notice eggs, baby birds and migratory storks. They visit a zoo and meet a jungle cat, an animal which is often killed during their annual hunting festival. They also watch a snake-rescue operation.

By the time this week-long experiment ends, the five boys are ‘transformed’ and one of them even hands over his catapult to Kapur saying he didn’t need it anymore. A month later, there is a ‘pop up’ exhibition of their photographs in the village and everyone is moved. Catapults To Cameras ends with an affirmation that children can be game changers and agents of change.

Meanwhile, RoundGlass Sustain has also partnered with Human & Environment Alliance League (HEAL), a local non-profit, and launched a conservation programme by the same name with a focus on rural youth to protect wildlife.

For me, I found parts of what the film wanted to convey, problematic. While the overall message of the film is on conservation and seeding change in minds of young children, the tone often came across as — the “uneducated” rural vs the educated urban messiah.

This has been a narrative that has been so mainstreamed by the media that almost all tribal and forest dwelling communities are seen as “destroyers”, “encroachers”, or “illegal”. I do not say that such hunting practices should not be condemned. But, storytellers should look at how they can sensitively approach such narratives.

The treatment of a sensitive story and the message it conveys is crucial. The film talks of how these villagers need to be “educated”. This is the danger of a single story and how that promotes certain stereotypes around adivasi communities and rural citizens of the country.

There is a moment in the film where complexity of living in proximity of forests emerges when a herd of elephants comes visiting a village signalling the increasing human-wildlife conflict. But that thread is soon lost.

As per the Census 2011, there are about 650,000 villages in the country, out of which nearly 170,000 villages are located in the proximity of forest areas. Nearly 250 million people live in and around forests in India, including about 100 million members of indigenous ‘Scheduled Tribes’. Some estimates claim that approximately 300 million people are dependent on forests. And often the adivasis and other forest dwellers get painted as “encroachers” or “hunters” or “uncivilised” to the global audience.

Have you liked the news article?