NEW DELHI: Since the Pahalgam killings, which brought Kashmir again in the spotlight, while the Kashmiri youth within the Valley and outside are navigating the harsh reality of being vilified, Jammu’s youth feel that they also get impacted due to media misrepresentations and misconceptions that have existed for years.

Two students and a professional from Jammu, presently based in Delhi, told the Kashmir Times that the nation-wide narrative after the Pahalgam attack impacts Jammu as well, though it resonates differently.

After the Pahalgam attack, many students from Kashmir studying in various cities across India were forced to leave their studies mid-way and go back to their homes following cases of harassment and attacks on them by mobs.

Media and Public Perception

Saksham, a 22-year-old journalist said that though he was not personally impacted, he added, “I guess part of the reason for that is I was born in a Hindu family in Jammu city, and I am not a Kashmiri Muslim.” Chaitanya, a 21-year-old student originally from Billawar in Kathua, currently studying law in National Law University (NLU), Delhi echoed the same sentiments.

However, Ali, also an NLU student, is more worried about broader consequences. Beyond the impact of individuals being harassed, he fears that some people will use the incident as a pretext to flare up communal tensions. “If it ends up destroying Kashmir’s tourism, it will have an economic impact which pushes people to desperation, and often makes them more inclined to anti-national activities.”

All three of them were deeply shocked by the Pahalgam incident that resulted in the killings of 25 tourists, who were selectively targeted for their religious identity, and a local pony operator who died while trying to protect the tourists.

"This came as a major shock,” said Saksham, adding, “Terrorists usually target army and police personnel, an attack on tourists is very rare.” Yet, a media perception across the country was created to vilify and demonise all Kashmiris.

“Unfortunately, Jammu also gets bracketed with that,” he says. “Within the region, it doesn’t impact Jammu, but outside in the rest of the country, the people rarely make a distinction between the two regions.”

All three highlighted a disparity in how Jammu and Kashmir are portrayed. Chaitanya said, “Yes. Not sure if within the state but definitely outside it.”

Saksham was more specific: “They are treated differently. Sometimes, Jammu is completely ignored in many of the media reports and coverage. Sometimes, it is just briefly mentioned or given very little space in the whole narrative of J&K.”

He noted that even Jammu’s coverage focuses on Dogri-speaking areas, sidelining Poonch-Rajouri or Doda-Kishtwar, and that Kashmir’s narrative is Srinagar-centric, ignoring rural districts like Ganderbal or Kupwara.

Ali added, “Kashmir is highly political, and in national politics, preference is given to them. As for Jammu, it has a different image, mostly because of its religious tourism.”

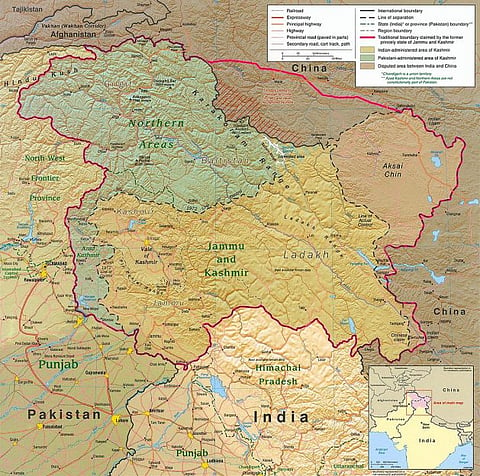

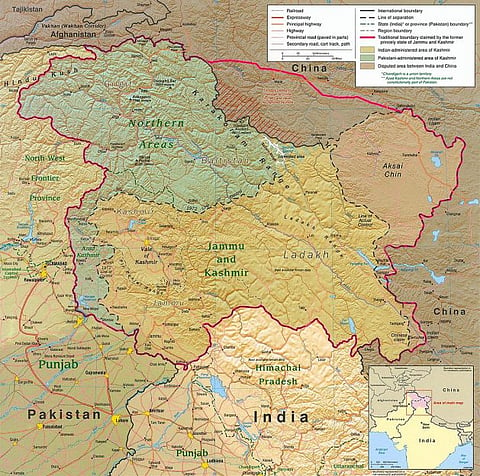

When Jammu and Kashmir is talked about, the conversation almost always pivots to Kashmir. This isn’t surprising. The Kashmir Valley has long been the epicentre of conflict, politics, and media attention. Often lost in this focus is the other half of the region—Jammu.

The term “Kashmir” is frequently used as shorthand for the entire Union Territory, but geographically and culturally, the region is divided into two major divisions: Kashmir and Jammu.

For those outside the region, “J&K” is often equated solely with Kashmir. But Jammu has its own identity—its own languages, history, and lived experiences.

What Jammu Wants Understood

Chaitanya emphasizes that Jammu has a distinct identity and calls for a broader understanding of both regions. “Jammu has its own cultural heritage and identity, the Dogras are a dominant ethnic group but there is much more.”

Saksham elaborates, “I want people to empathise with us. I want them to understand that the situation on the ground is not so black and white or simple as it is in their minds.” Jammu is diverse, he says.

Talking about Jammu’s diversity, he says, “J&K is a state home to Kashmiris, Gujjar-Bakarwals, Poonchis, Bhaderwahis, Kishtwaris, Ladakhis, Dogras and many more ethnic groups… Jammu in particular is one of the most unexplored, ignored, diverse, and culturally rich regions in India.”

On Jammu city’s aspirations, Ali adds, “Jammu is a secular, peace-loving town with people who have humble aspirations. It is not a place where terrorism is endorsed or supported. However, in recent times, Jammu has become highly polarised.”

Added to that is the baggage of uncertainty. Chaitanya and Saksham speak about the curfew restrictions and internet disruptions that are often imposed due to the conflict.

“After I completed Class 12th in 2020, I got admission in a university outside J&K, but then the lockdown got extended… There was an internet shutdown in J&K following the abrogation of Article 370.” Unable to attend online classes, he took a gap year.

Ali adds, “Such incidents create a lingering sense of uncertainty and anxiety, affecting emotional well-being. They can disrupt travel, communication, and sometimes cause delays in academic or professional commitments.”

A bigger issue, points out Chaitanya, is that “the stereotypes that people outside J&K have for Jammuites are the same as they have for Kashmiris…… Ironically enough, I think Kashmiris stereotype the people of Jammu even more, but well that goes for both sides.”

Saksham says, “Most people don’t know the difference between Jammu and Kashmir… so they use the same stereotypes of calling me a stone pelter or anti-national as they use for Kashmiris.”

Saksham laughs at the irony, “My friends still call me Kashmiri even after knowing I am from Jammu.”

Ali agrees and adds, “People often assume I come from a conflict-ridden or militarized area and fail to recognize that Jammu has its own unique identity, separate from Kashmir.”

“Outsiders often perceive Jammu and Kashmir as one monolithic entity, ignoring the cultural, historical, and socio-political differences. I believe it’s important to acknowledge both the shared and distinct experiences of each to truly understand the region,” says Ali.

Outsiders often conflate the two regions. Chaitanya said, “Some don't know the difference between the two. Some who are more aware that Jammu has an identity also don't know much about it.”

Their regret is that in any discourse on J&K, Jammu is reduced to a footnote.

Talking about the distinct identities and its understanding within the Union Territory, they say there are more divisions, than a sense of being from a cohesive unit comprising various sub-units/cultures. “I think all of them have this sort of otherness about each other,” says Chaitnya.

Ali noted, “Many youth from Jammu see J&K as a politically bound region but recognize the deep cultural and regional differences within it. While they value the shared history, there’s also a growing sense that Jammu’s identity is often overshadowed in broader narratives about the state.”

Despite this, Ali envisions a future for the Jammu region. “I hope for a peaceful and stable future where the youth are empowered through education and opportunities, and the region is recognised for its culture, potential, and contributions beyond politics.”

Have you liked the news article?