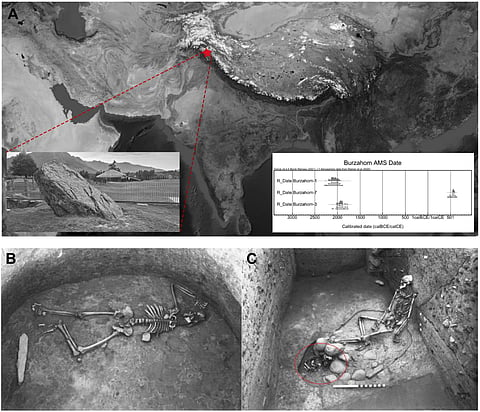

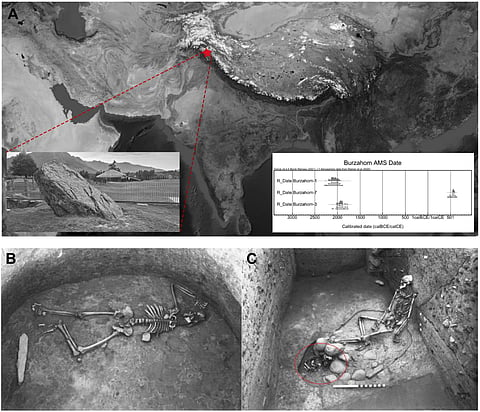

NEW DELHI: In a groundbreaking discovery, Indian and Kashmiri scientists have successfully reconstructed ancient DNA from human burials at Burzahom — one of South Asia’s earliest Neolithic sites near Srinagar.

The study, published in Scientific Reports by researchers from the Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeosciences and the University of Kashmir, traces Kashmir’s maternal ancestry over 7,000 years, revealing that the people who lived here shared genetic links with populations as far as Central Asia, the Swat Valley, and Europe.

Burzahom, meaning “place of birch,” is nestled between the Himalayas and the Pir Panjal range. It has long fascinated archaeologists with its pit dwellings, tools, and burials that suggest one of the oldest farming communities in the region.

Excavations show that it was inhabited from 2900 BCE to about the 5th century CE. But until now, there was little direct genetic evidence to back up what archaeologists had long suspected — that Kashmir stood at the crossroads of ancient civilisations.

The study examined 12 skeletal remains from Burzahom, ranging from the Neolithic (around 2000 BCE) to the medieval period. Four of them yielded enough mitochondrial DNA — the genetic material passed through mothers — to build full ancient genomes.

One Neolithic sample, nearly 4,000 years old, carried a maternal lineage called M65, found mainly in modern Kashmiris and Tajiks of the Pamir Plateau. This points to long-standing local ancestry, possibly dating back 7,000 years.

Another sample from the Megalithic period (around 550 CE) belonged to the U2b2 lineage, which also appears in modern Kashmir, Pakistan’s Swat Valley, and Central Asia — again suggesting continuity.

The two medieval samples, however, showed wider links. One carried the M30 lineage, common in Kashmir, Pakistan, and western India, but also related to a mysterious group found in Roopkund Lake, where medieval travellers perished in the Himalayas.

The other carried W4, a lineage more typical of Central Asia and Europe — appearing in ancient cultures like the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC) in present-day Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan.

“These findings show that while early Kashmiris were genetically rooted in the region, later periods saw clear contact with Central Asia and beyond,” said lead author Dr Niraj Rai of the Birbal Sahni Institute.

The analysis aligns with archaeological evidence showing Burzahom’s cultural connections to the Swat Valley and the Indus region. Pottery styles, stone tools, and even burial customs mirror those found in northern Pakistan and Central Asia.

The Neolithic people of Burzahom were farmers and herders who lived in pit houses, used birch bark for roofing, and sometimes buried animals with humans — suggesting early rituals of companionship or sacrifice.

Later, megalithic and early historic communities added new technologies and external influences, as trade routes opened across the Himalayas.

The study’s authors note that the valley’s position — between Central Asia, Tibet, and the Indian plains — made it a natural corridor for movement, trade, and migration. Genetic evidence now confirms that Kashmir’s population absorbed these influences while maintaining ancient maternal roots.

In their analysis, scientists compared Burzahom DNA with both ancient and modern genomes from across Asia. They found that the Neolithic Kashmiri sample (M65) closely matched the Brokpa tribe of Ladakh and the Scheduled Caste groups in Kashmir today.

Its genetic age — around 7,000 years before present — suggests an unbroken maternal line within the broader Indo-Tibetan and Indo-European population structure.

The U2b2 lineage from the Megalithic sample appeared in both Swat Valley Iron Age remains and among north Indian Brahmins, hinting at common ancestry or long-distance cultural contact.

The medieval W4 lineage, on the other hand, connected Kashmir to Bronze Age Central Asia and Europe — places like Italy, Finland, and Poland, where the same haplogroup appears in low frequencies today. That makes this Kashmiri individual one of the few known South Asian links to western Eurasian maternal ancestry from ancient times.

According to the study, Kashmir’s genetic story combines two threads: deep local continuity and episodic contact with distant lands. For at least 7,000 years, maternal DNA in the valley shows steady persistence — suggesting that the women who lived, worked, and gave birth here were part of the same broad genetic family through millennia. Yet, migrations and trade introduced new lineages, especially during medieval times, when Kashmir’s culture and economy became more cosmopolitan.

“The genetic signatures mirror the valley’s history as both isolated and connected — a unique blend of deep roots and open doors,” the researchers wrote.

This is the first ancient DNA study from Kashmir and among the very few from South Asia. The region’s climate makes DNA preservation difficult, so successful sequencing marks a technical achievement. The findings open the door for broader archaeogenetic mapping — connecting India, Pakistan, Tibet, and Central Asia through shared ancestry.

Globally, it also adds to our understanding of how early humans spread across Eurasia. The M65 and U2 lineages found in Kashmir have counterparts in Central Asian, Iranian, and even European populations. In Europe, for instance, U2 and W haplogroups appear in Neolithic and Bronze Age remains from Germany and Poland, showing ancient east-west gene flow. In Central Asia, similar DNA types appear in Tajiks, Uyghurs, and BMAC samples — evidence of a long corridor of human movement.

This suggests that the Himalayas were not barriers but bridges, linking people from the steppes to South Asia. Kashmir, sitting at that intersection, served as a melting pot where ideas, crops, and genes all met.

The study’s radiocarbon dating places the Burzahom remains between 2000 BCE and the Middle Ages. The Neolithic skeletons were found in pits, sometimes painted with red ochre or buried with animals — practices also seen in other prehistoric cultures from Europe to China.

One skull even showed signs of trepanation — early brain surgery — indicating a surprisingly advanced understanding of anatomy.

Such cultural parallels, together with the genetic findings, underline Burzahom’s role in global prehistory. It was not an isolated mountain village but part of a vast human web stretching from the Indus to the Altai.

Bigger Picture

The DNA evidence from Kashmir resonates with findings elsewhere in Asia. Similar mitochondrial lineages have been found in:

Swat Valley (Pakistan) – Iron Age burials linked to Indo-Iranian expansion

BMAC region (Central Asia) – Bronze Age urban settlements that traded with the Indus Valley

Roopkund Lake (India) – Medieval travellers from diverse origins, possibly passing through the Kashmir routes

European Neolithic sites – Early farmers carrying U2 and W haplogroups eastward

Together, these links reinforce the idea that the Kashmir Valley was not a remote outpost but a dynamic hub of early human migration and exchange.

Researchers hope future DNA studies from other Kashmiri sites like Gufkral, Kanispora, and Baramulla will fill gaps in this emerging map. With advances in ancient DNA extraction, scientists can now retrieve genetic material even from fragile bones — offering insights not just into ancestry, but diet, disease, and migration.

For Kashmir, this means rewriting parts of its prehistory with evidence rather than assumption. As Dr Mohammad Ajmal Shah from the University of Kashmir noted, “These findings confirm that our ancestors were not isolated. The Valley was always part of a wider human story — one that stretched from the Indus to the Silk Road.”

From birch-covered Neolithic pits to medieval crossroads, Kashmir’s DNA record tells a tale of both belonging and encounter. It affirms that the people of this valley, while shaped by many influences, carry within them one of the world’s oldest continuous maternal lineages.

The study also reminds us that the soil of Kashmir — where every layer reveals another chapter of civilisation — holds keys not just to its own past, but to the shared human journey across continents.

Have you liked the news article?