First person account:

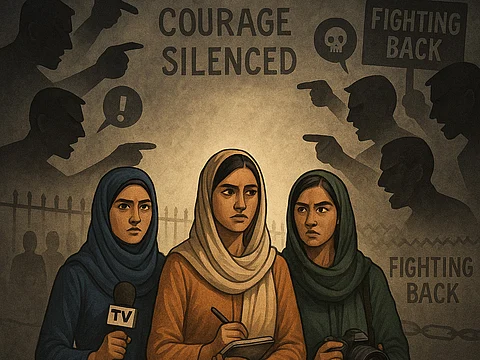

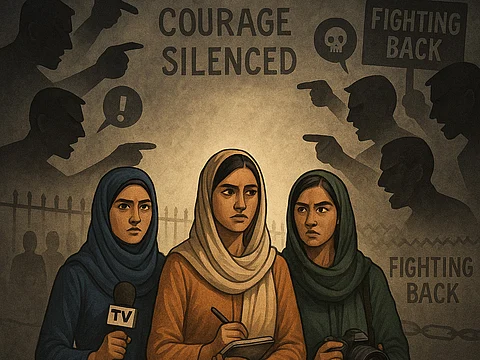

Like other South Asian cities, being a working woman is a challenge in Muzaffarabad, the capital of Pakistan-administered Jammu and Kashmir. But for women in male-dominated professions—particularly journalism—this challenge becomes a daily struggle for safety, dignity, and sanity.

When a woman steps into a newsroom here, especially in a reporting role that requires public visibility, fieldwork, and interviews, she does not just have to prove her competence. She has to endure unspoken rules: men taunt, they fixate, they whisper. Just walking into a press club or attending a press conference is enough to invite stares, unsolicited comments, and character judgments. Her presence is treated not as professional, but as provocative.

I speak not only from observation, but from deeply personal experience.

I began my journalism career in the Pakistani capital, Islamabad. Like many young professionals, I was driven by purpose and passion. I believed journalism was a public service, and that women could—and should—be part of the democratic process of storytelling. A few years ago, I moved back to Muzaffarabad, my hometown, eager to contribute to its media landscape and find my voice.

I was new, learning the ropes, finding my footing. I made some early mistakes—nothing out of the ordinary for a young reporter—but instead of mentorship or even healthy competition, I became the target of a vicious smear campaign orchestrated by male journalists who simply could not tolerate the presence of a confident, independent woman in their midst.

The attacks began with whispers and mocking comments. Then came the online bullying. The harassment finally escalated into something far more sinister: character assassination in print.

One local reporter crossed every boundary of journalistic ethics and decency. In a Muzaffarabad-based Urdu daily, he wrote a vile, defamatory piece. Though he did not name me directly, the implication was unmistakable.

He used the term “divorced woman” as a slur, weaponising my personal life to portray me as morally suspect, because in his view, a woman’s worth begins and ends with her marital status.

He did not stop there. He shared the article on social media, tagging mutual contacts and inserting vague but toxic references to my work. The message was clear: I was to be discredited, shamed, and silenced. When I investigated further, I discovered he had once sent me a message on WhatsApp, which I had ignored. That single act of non-response seems to have triggered a campaign of stalking and vindictiveness.

Even more disturbing was the reaction—or utter lack of it, from the local journalistic fraternity. Instead of standing by me, many rallied around him. When I filed a police report to protect myself, he arrived at the police station flanked by fellow journalists. Some of these same men—who speak eloquently about press freedom and democracy—tried to convince me to withdraw the case. They did not once ask him to apologise or be accountable.

The backlash was brutal. I was interrogated by my peers, accused of “going too far,” and told I was jeopardising the press community by daring to seek legal redress. The harasser was shielded by a toxic boys’ club that thrives on patriarchy and impunity.

I also submitted a formal complaint to the Azad Kashmir Press Foundation, along with documentation of the harassment. This government-funded body is meant to protect journalists and uphold ethics. Instead, my confidential documents were leaked, most likely by someone within the Foundation. The same journalist who harassed me is now distributing my personal information across WhatsApp groups and Facebook pages, further violating my privacy and dignity.

This is no longer about one article or one man’s vendetta. This is a systemic effort to silence a woman who dared to work, speak, and defend herself.

The psychological impact has been devastating. I have experienced severe anxiety, insomnia, and episodes of depression. I have lost the ability to trust my colleagues. The passion I once felt for journalism now feels burdened by fear—fear of another attack, another lie, another betrayal. Every time I walk into a press briefing or take on a story, I brace myself for backlash.

And what has been the response from the institutions meant to protect us? Nothing. Not a single media organisation in Azad Kashmir (Pakistan administered Jammu & Kashmir) has offered support. Not one editor has condemned this campaign of hate. Not one peer has offered public solidarity.

The only organisation that has stood by me is Freedom Network, a Pakistan-based media rights watchdog. Its unwavering support—legal, emotional, and professional—has been my only source of strength. They have helped me navigate this storm with courage, guiding me through court procedures, digital security protocols, and emotional healing. Their presence reminds me that I am not entirely alone.

But I should not have to depend on one organisation for something so basic as justice.

My case is not unique. Many women in Azad Kashmir (PaJK) — be they journalists, lawyers, or rights activists—have suffered in silence. Some leave the profession. Others are broken emotionally. Very few speak out, knowing what awaits them if they do.

But I choose to speak because silence protects the perpetrators.

This is not just a story about workplace harassment. It’s about a patriarchal culture that refuses to accept women as equals in public life. It is about media institutions that prize loyalty to their male colleagues over justice for women. And it is about a society where a woman must think twice before replying to a message, before reporting a story, before existing in public.

So I ask again:

Why do we still tolerate this misogyny?

Why are women told to stay silent in the face of harassment?

Why do institutions fail the very people they are meant to protect?

I may be scarred, but I am not defeated.

I will not be shamed into silence. I will continue to report, to write, and to defend the right of every woman in Azad Kashmir (PaJK) to live and work with dignity.

Not just for myself, but for every woman who has been told to stay in her place.

(Nosheen Khawaja, a journalist based in Muzaffarabad, writes occasionally for Kashmir Times, hosts podcasts for Kashmir Digital Media)

Have you liked the news article?