(Editor’s Note: This column is the first in a ten-part series by journalist and writer Ira Mathur, exploring the Kashmiri poets and writers who have given voice to a people silenced by history and conflict. Through their words, they have preserved memory, defied erasure, and borne witness when Kashmiris themselves could not speak.)

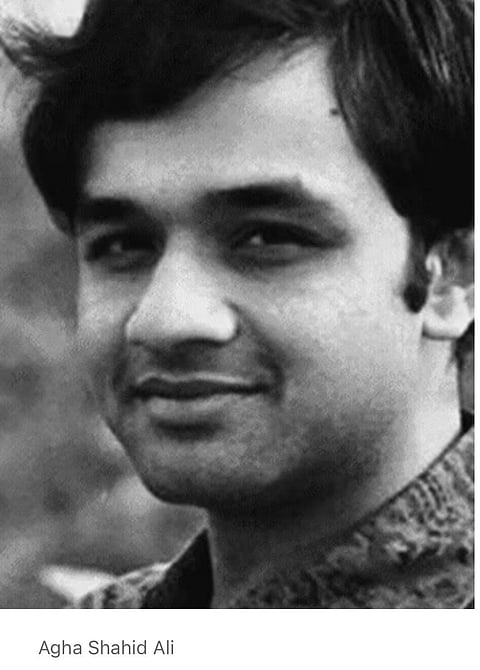

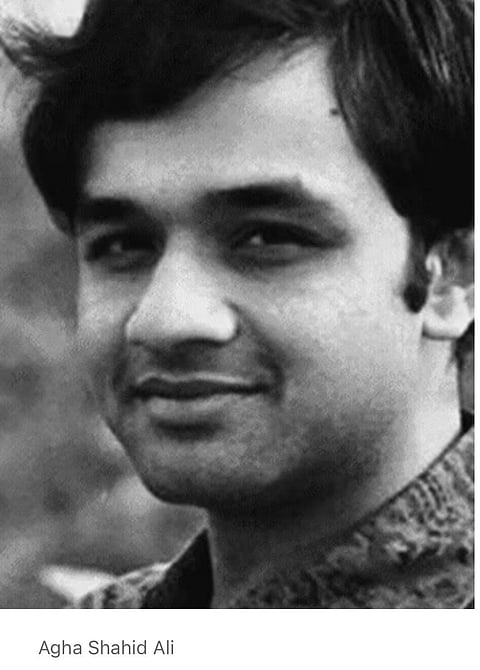

Few poets have captured the soul of Kashmir with as much precision and sorrow as Agha Shahid Ali. Born in 1949 in New Delhi and raised in Srinagar, he bore witness to a land that has, for generations, been trapped between longing and loss.

His poetry bridges the personal and the political, between nostalgia and a brutal present. He wrote of silences that deepen, of voices that vanish, of a paradise unmade by history.

To read him is to enter the dream of Kashmir — snow-laden mountains, the scent of saffron, the shimmer of Dal Lake — only to wake to the sound of gunfire, the glare of soldiers, the weight of curfews and mass graves.

Bearer Of A Brutal Past

For centuries, Kashmir was a crossroads of empire — claimed by the Mughals, the Afghans, the Sikhs, and then the British. Partition in 1947 only deepened its fracture, with India and Pakistan turning the valley into a contested battleground. In this place, sovereignty was decided not by the people who lived there but by forces that saw it as a prize, a pawn in larger geopolitical struggles.

In 1949, the year of Ali’s birth, the United Nations brokered a ceasefire that left Kashmir divided, a volatile border splitting families, histories, and futures.

By the late 1980s, this limbo erupted into open conflict. What began as a movement for self-determination was soon met with overwhelming military force. The streets of Srinagar, once lined with bookshops and bustling markets, became ghostly under curfew.

Armed insurgents fought Indian forces, the valley filled with checkpoints and security bunkers, and disappearances became routine. The people of Kashmir, caught in the crossfire of insurgency and counter-insurgency, learned that their voices could be silenced in an instant.

This is the Kashmir that Ali carried within him, the one he immortalized in The Country Without a Post Office (1997), a collection written after the valley was thrown into near-total isolation. The title itself is drawn from the real-life event of the 1990s when postal services were suspended due to the conflict.

For Ali, this was more than an inconvenience — it was a metaphor for the larger erasure of Kashmiri identity. Letters went unanswered, the dead went uncounted, the past was rewritten.

"At a certain point I lost track of you.

They make a desolation and call it peace."

That line remains chillingly relevant. In August 2019, the Indian government, led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, revoked Article 370, stripping Jammu and Kashmir of its special status. The state, already heavily militarized, was placed under an unprecedented lockdown.

Tens of thousands of troops were deployed overnight. Internet and phone services were shut down. Journalists were detained; political leaders placed under house arrest. A new set of laws was introduced, allowing non-Kashmiris to buy land, exacerbating fears of demographic engineering. The valley fell silent—not out of peace, but out of suppression.

Since then, Kashmir has existed under a veil of control. Over 500,000 Indian security personnel patrol its towns and villages, making it one of the most militarized zones on earth.

Between 2020 and 2024, over 350 civilians have been killed, including political activists, lawyers, Kashmiri Pandits and migrant workers. The nature of insurgency has shifted; where once it was driven by separatist groups, now small, well-trained militant cells execute targeted assassinations.

Reports suggest that these new actors have access to advanced weaponry, hinting at shadow wars beyond Kashmir’s borders. The violence no longer follows the old patterns — it has evolved, and with it, the methods of control have grown more insidious.

If Ali were alive today, his poetry would mourn not only the soldiers at every street corner but also the quieter forms of suffocation. This bureaucratic red tape denies Kashmiris land, education, travel. The digital surveillance tracks every movement. The rewriting of history in textbooks erases the lived realities of occupation.

If he were alive today, his metaphors of silence—vanished homes, censored voices, unwritten letters—would feel less like poetry and more like documentation.

Ode To Exile

Yet exile, another of his obsessions, remains the truest metaphor for Kashmiri life. The Pandits who fled the 1990s insurgency remain scattered across India, their longing unfulfilled. The families of the disappeared still search for their dead. The poets who write about Kashmir do so from a distance, their verses smuggled in, their words met with scrutiny. Even Ali himself never returned.

In The Last Saffron, he wrote:

"I will die, in autumn, in Kashmir,

and the shadowed routine of each vein

will almost be fulfilled."

But he did not die in Kashmir. And many Kashmiris will never return to the place they left behind. Their exile is not just geographic but existential, a perpetual longing for a home that no longer exists.

Ali was also a master of the ghazal — a poetic form built on repetition, on echoes. The ghazal’s structure — each couplet standing alone, yet part of a greater lament — mirrors Kashmir’s own history. The same sorrow, the same struggle, retold in different decades.

Today, younger Kashmiri poets continue this tradition, using poetry as an act of defiance. Their words bear witness to a place that refuses to disappear, no matter how often it is silenced.

Yet Ali’s poetry is not only about Kashmir. It belongs to all those who have lived in exile, whether forced or self-imposed. His verses resonate with Palestinians, Tibetans, Uyghurs, Rohingya — the stateless millions who carry a home within them that they will never see again.

His poetry speaks to those who have seen their histories rewritten, their lands taken, their voices drowned out by the machinery of power.

Ali did not write to be a historian but to remind us that poetry itself is an act of remembering. That, to name grief, is to defy erasure. That to write is to refuse silence. His work does not allow us to look away. It does not offer comfort or resolution.

It leaves us, instead, with questions:

What is left of home when even its echoes are censored?

Who delivers the letters of the disappeared?

What happens when a people’s longing is the only thing that survives?

Agha Shahid Ali’s Kashmir is not a memory but an unanswered question that still demands to be heard.

(Ira Mathur, daughter of a Hindu Indian Army officer and a Muslim mother, is an Indian-born multimedia journalist based in Trinidad. In July 2024, Speaking Tiger Books acquired the South Asian rights to her memoir, "Love The Dark Days".)

Have you liked the news article?