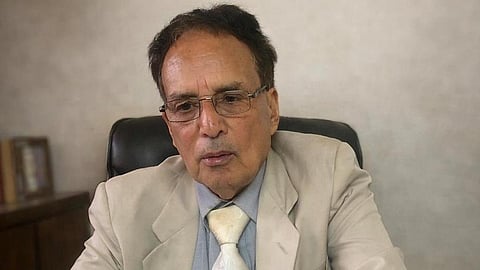

Prominent social and political activist Pandit Bhushan Bazaz, head of the Jammu and Kashmir Democratic Front (JKDF), died in New Delhi after a prolonged illness. He was 91.

Bazaz’s identity was that of the son of Prem Nath Bazaz, one of the most consequential figures in modern Kashmiri history. Yet he earned wide respect in his own right as an advocate of brotherhood and Kashmiriyat, and a tireless believer in peace, reconciliation, and dialogue.

He lived in South Delhi’s Hauz Khas. His home became a Delhi refuge for Kashmiri leaders, especially Mirwaiz Umar Farooq and members of his family. The first floor was set aside for them. Because my route to the office passed through his colony, he would call every 10 or 15 days, whenever he had a break from hosting visitors, and insist I stop for tea and breakfast.

Those conversations ranged from current affairs to priceless recollections about his father.

Every year on July 13, as Kashmir remembered the martyrs of 1931, Bazaz would also mark his father’s birthday at home with close friends and family, keeping alive a parallel memory of sacrifice and conscience.

In 2000, he travelled to Pakistan to attend the wedding of Sajjad Gani Lone and Asma Khan, daughter of JKLF leader Amanullah Khan. While there, he asked to visit Mirpur in Pakistan-administered Kashmir.

Reaching late at night, he insisted on seeing the old jail where Dogra rulers had imprisoned his father. The jail, he was told, lay submerged under the Mangla Dam. Undeterred, he took a boat in the dark, reached the site, and brought back a few broken bricks. At the Wagah–Attari border, customs officials subjected the bricks to X-ray scans and even broke one, suspecting contraband. A few managed to survive the scrutiny and made it to Delhi. Bazaz framed them near the small temple in his home and showed them with quiet pride.

Tragedy struck in 2004 when his young son, Gaurav Bazaz, was shot dead in Toronto. In 2010, Canadian police arrested Vijay Singh in connection with the killing, but the motive remained unclear.

Indelible Imprint on Kashmir

His father, Prem Nath Bazaz, a journalist by training, left an indelible imprint on Kashmir’s politics. It is widely held that his influence persuaded Sheikh Abdullah to rename the All Jammu and Kashmir Muslim Conference as the National Conference to allow Pandit participation. Yet, despite being a Pandit, Bazaz soon drew closer to the Muslim Conference.

In 1932, he launched the daily Vitasta Kashmir. Later, with Abdullah, he founded Hamdard. The partnership did not last. Bazaz turned Hamdard into a virtual organ of the Muslim Conference and began writing sharply against Abdullah and the National Conference.

On April 11, 1947, Prem Nath Bazaz survived an assassination attempt. Two men were arrested, but after Abdullah became the emergency administrator, the court acquitted them.

On October 21, 1947, Bazaz himself was arrested by the emergency administration and jailed for three years. During Abdullah’s tenure as prime minister, he was forced into exile in New Delhi, barred from entering Kashmir. He built a home in the Hauz Khas locality. Sheikh charged that Pakistan had financed the construction of his home.

In his autobiography Atish-e-Chinar, Sheikh Abdullah offered a barbed assessment of Bazaz, calling him intelligent, politically perceptive, and capable of raising his voice for justice, but accusing him of inconsistency and a love of money. The charge, many would note, echoed allegations often levelled at Abdullah and his family as well.

Bazaz wrote in 1954: “Kashmir belongs to Kashmiris, and neither the Maharaja nor any outsider, however powerful, has the right to impose decisions about its future.”

His stand against injustice made him vulnerable even within his own community, many of whom were invested in Dogra rule. After opposing the 1975 accord between Indira Gandhi and Sheikh Abdullah, he became part of a structured alliance influenced by Mirwaiz Farooq’s Awami Action Committee.

When Muhammad Ali Jinnah visited Srinagar in May 1944, he praised Prem Nath Bazaz in an interview with journalist J.N. Sathu, saying figures like him could draw Kashmiri Pandits into national politics and mobilize them against autocracy.

An editorial Bazaz wrote on June 10, 1947, remains striking. He argued that Hindus did not support the National Conference out of affection but out of hostility toward Muslims, and that a handful of Hindu members did not make the party representative of minorities.

In his book History of the Struggle for Freedom in Kashmir, published in March 1952, he warned that unmet aspirations of Kashmiri youth would one day push them to take up arms. Three decades later, events proved prophetic.

Born on July 13, 1905, Prem Nath Bazaz had four sons and five daughters. It was Bhushan Bazaz who carried his political legacy forward, although he could not match his father’s legacy. A realist among Kashmiri Pandits, Prem Nath Bazaz recognized that the end of Dogra rule was near and helped build a common platform with the Muslim community. Unfortunately, today, Kashmiri Pandits and Muslims share no comparable social or political project.

Glancy Commission

After the 1931 uprising and the killings that followed, Bazaz told the Glancy Commission that Muslim grievances were justified, even though this weakened the claims and privileges of his own community. He was beaten by fellow Pandits and forced to leave the Pandit-majority area of Zindapora for a house in Abi Guzar.

Bhushan Bazaz preserved his father’s diaries but resisted repeated requests to publish them.

He once told me that Jawaharlal Nehru had offered his father one of two general secretary posts in the States People’s Conference, which Nehru headed, but Bazaz declined, saying his work lay in Kashmir.

Farooq Abdullah later recalled that Sheikh Abdullah and Bazaz were fundamentally divided on the issue of Accession.

Exile in Delhi and the ban on his return to Kashmir embittered Prem Nath Bazaz, though he wrote to Nehru expressing willingness to work with Kashmiri Muslims to accept autonomy for Jammu and Kashmir as an alternative option.

A lifelong student of history, Prem Nath Bazaz authored more than a dozen books. He believed Kashmiri Muslim political awakening was part of a broader subcontinental expression, and envisioned a society where neither Pandits nor Muslims dominated the other.

His life, and his complex relationship with Sheikh Abdullah, disproved the notion that a Kashmiri Pandit must be unambiguously pro-India and a Kashmiri Muslim pro-Pakistan.

As Kashmir passes through one of its most fragile and difficult moments, the absence of figures like Prem Nath Bazaz and his son Bhushan Bazaz, who kept that ethical inheritance alive, feels especially stark.

Have you liked the news article?