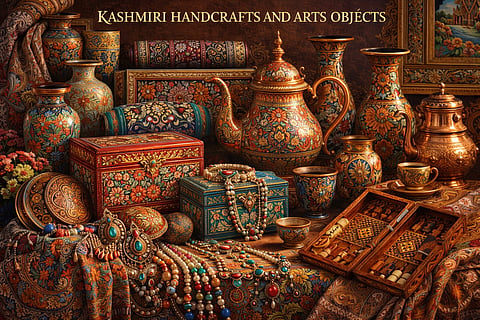

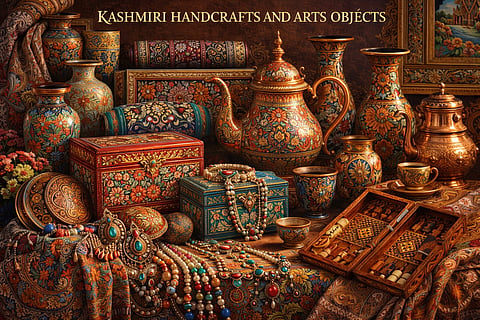

For generations, Kashmir has produced some of the world’s finest natural and artisanal goods. Pashmina shawls, crisp apples, deep-red saffron, walnuts, almonds, hand-knotted carpets, fragrant flowers, and medicinal plants have long travelled beyond the valley. Yet a familiar paradox remains: Kashmir produces excellence but rarely owns the brand. The value is often captured elsewhere.

This disconnect between production and branding is not accidental. It reflects decades of structural neglect, the absence of certification systems, and a lack of institutional mechanisms that allow producers to claim ownership of their heritage in global markets.

During my tenure as president of the Kashmir Chamber of Commerce and Industry from 2006 to 2009, we recognised that survival in a globalised economy required more than tradition. It required branding, certification, and protection of origin. That realisation led to the initiation of the Geographical Indication process for Pashmina. We worked to build an institutional structure that could own the brand, set up testing and labelling systems, and resist attempts from outside to dilute authenticity.

The effort was not easy. We had to begin from scratch, creating a dedicated NGO structure, designing authentication protocols, and laying the foundation for what later evolved into QR-based traceability. Today, such a system can identify not just the product, but even the artisan behind a Pashmina piece. That experience taught a simple but powerful lesson: heritage without institutional branding is economically vulnerable.

The contrast between Pashmina and the globally marketed “cashmere” illustrates this vulnerability. Authentic Kashmiri Pashmina is finer and rarer than most products sold worldwide under the Cashmere label. Yet in international markets, the word “Cashmere” commands higher prices and stronger brand recognition, while the original source struggles for visibility. European manufacturers historically sourced raw material from this region, but built global brands around it. Kashmir remained a supplier. Others became owners of the narrative.

The introduction of GI protection and QR-based authentication was meant to reverse this value inversion. But the impact has been limited by the failure to expand testing and certification centres into the districts where production actually happens. Brand protection must reach the artisan’s doorstep, not remain confined to central facilities.

The same structural weakness is visible in the apple fruit economy. Kashmir exports fresh fruit but imports processed value. Most of the profit lies not in growing apples but in turning them into juices, concentrates, cider, dried fruit, and branded consumer products. Diversification into these sectors can multiply farmer income. Walnuts, almonds, and even dairy offer similar opportunities. With origin-based organic branding, these products could position Kashmir in premium markets across Asia, Europe, and the Gulf.

The lesson is simple: processing combined with branding creates economic resilience.

Floriculture

Perhaps the most overlooked opportunity lies in floriculture. Kashmir’s climate and soil give it natural advantages in tulips, lavender, roses, saffron flowers, and a range of medicinal and aromatic plants. The global wellness and essential oils market is expanding rapidly, driven by demand for traceable, natural, and origin-based products.

A unified “Flowers of Kashmir” brand could bring together lavender and rose oils, dried flowers, herbal teas, natural cosmetics, and even tulip bulbs for export. This sector is especially suited for women and youth entrepreneurs. It requires relatively small landholdings, offers high value per acre, and can be integrated into rural livelihoods.

At present, tulips generate seasonal tourism imagery, but not a structured export economy. The Netherlands transformed tulips into a multi-billion-dollar industry through branding, logistics, and global marketing. Kashmir still treats its floral wealth as a seasonal attraction rather than an economic pillar.

This is why branding must be understood not merely as a marketing exercise, but as an economic rights framework. It protects artisans from imitation. It ensures farmers receive premium prices. It creates employment beyond government dependency. And it anchors cultural identity in global markets.

A coherent Brand Kashmir architecture would integrate several sectors: Pashmina backed by GI and QR traceability; apples linked to processing and global retail branding; nuts and dairy positioned as organic, origin-based exports; and floriculture connected to wellness and luxury markets.

None of this can succeed without the active involvement of the Kashmiri diaspora. Communities in the United Kingdom, Europe, the Gulf, and North America possess capital, networks, and market access. They can invest in processing and branding infrastructure, build retail and e-commerce platforms, and serve as custodians of authenticity abroad. Diaspora-led luxury retail and traceable supply chains can help reposition Kashmir from a conflict-associated geography to a heritage luxury origin.

To move from vision to reality, several steps are essential. GI testing and QR certification centres must be expanded to all production districts. Processing clusters for apples, nuts, dairy, and floriculture need to be established. A unified Brand Kashmir export platform should be created. Diaspora investment funds must be encouraged to support value-added industries. Young entrepreneurs should be integrated through startups in design, e-commerce, and wellness products.

Kashmir does not lack products. It lacks ownership of its narrative and value chains.

Branding Kashmir is not about logos or slogans. It is about economic dignity, cultural preservation, and global positioning. The foundations were laid years ago. What is needed now is scale, institutional continuity, and a partnership between local producers and a global diaspora. Only then can Kashmir move from being a source of raw heritage to a recognised origin of premium value.

Have you liked the news article?