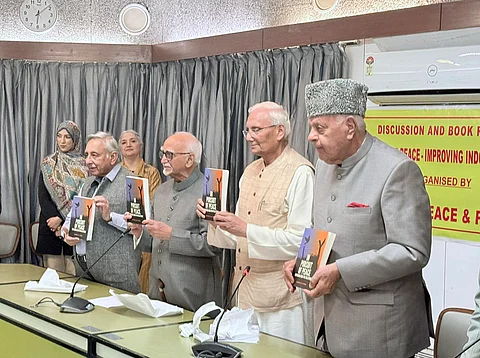

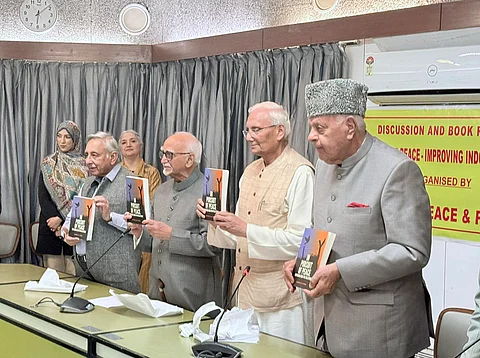

A recent cross-border conference convened in New Delhi by veteran peace advocate O P Shah offered a rare, if understated, sign that at least at non-official expert levels India and Pakistan are willing to reopen channels of dialogue—however cautiously.

Featuring former diplomats, politicians, and retired military officials from both countries, the event was notable not for any dramatic breakthrough, but for its tone, timing, and quiet symbolism.

Pakistani delegates, though restricted to virtual participation due to prevailing diplomatic constraints, were part of wide-ranging conversations that challenged the hardened rhetoric of recent years. Even if such conferences do not result in immediate policy change, they often act as bellwethers—nudging discourse away from belligerence and back toward engagement.

In a region perennially poised on the edge of catastrophe, small gestures matter. And the fact that such an event was permitted in the political heart of India signals a degree of openness, however measured, to rethinking the ‘no-talks’ approach that has dominated in recent years.

The timing could not have been more pertinent. The region has only just stepped back from the brink following a tense military standoff. The rhetoric on both sides has remained inflammatory, and New Delhi’s unilateral revocation of Jammu and Kashmir’s constitutional status in 2019 continues to cast a long shadow.

Against this backdrop, the Delhi conference served as a modest but meaningful pause. Participants discussed a broad set of regional issues, with a particular focus on Kashmir. There were calls for the restoration of constitutional guarantees such as Articles 370 and 35A, the return of statehood to Jammu and Kashmir, and—critically—the resumption of people-to-people contact and communication channels.

There was a clear recognition that military solutions are not only futile but dangerously short-sighted. What is needed instead is statesmanship, pragmatism, and a willingness to include Kashmiri voices—long marginalised in this dialogue.

Why does it matter?

Since 2019, both formal and informal diplomatic channels have largely broken down. The ensuing silence has allowed hawkish voices on both sides to fill the vacuum, fuelling further hostility and mistrust. In this context, the Delhi gathering—though limited in scope—offered a crucial platform for civil society voices to reassert the value of dialogue.

Such exchanges, even when unofficial, can help reduce the trust deficit and re-energise constituencies that have long championed peace at great personal cost. However, one must not mistake symbolic progress for substantive change. Without high-level political will—especially from India—these efforts will remain peripheral.

India’s insistence on linking dialogue with terrorism concerns has repeatedly stalled any structured engagement. As a result, outstanding disputes—particularly Kashmir—remain unresolved, festering into deeper insecurity and volatility.

Track-II diplomacy, which involves some sanction from official channels once a useful tool for breaking deadlocks, has been actively discouraged in recent years—especially by New Delhi. Once-promising initiatives have struggled for relevance as political space has shrunk and nationalism has become ascendant. While individuals like O P Shah and institutions like the Jinnah Institute have kept the flame alive, their efforts in recent times have rarely translated into any policy impact.

India’s entrenched position on Kashmir as an “integral part” of the Union leaves little room for honest engagement. Meanwhile, the region continues to reel under a heavy security footprint, with freedoms curtailed and political voices muzzled. The consequences have been grave—deepened alienation, rising despair, and the steady erosion of democratic space.

Push for institutionalised dialogue

The Delhi conference is no panacea for the deeply entrenched problems facing South Asia. But it does suggest a possible thaw—an opportunity, however tentative, as every participant urged for rethinking the current impasse, implying that all measures taken post August 5, 2019, have not worked.

What came out of the meeting is that participants agreed that dialogue must be institutionalised. That means creating a structured, inclusive, and durable framework for talks—one that is shielded from electoral cycles and the vagaries of domestic politics. They called for reviving Track-II and back channel efforts, which must be complemented by Track-I commitments grounded in political will and diplomatic seriousness.

Any peace process that sidelines the people of Jammu and Kashmir is doomed to fail. For decades, talks have been conducted over Kashmir, not with Kashmiris. This exclusion has delegitimised proposed solutions in the eyes of those who live with the conflict daily.

Kashmiris—across all communities and regions—must be recognised as essential stakeholders. Their aspirations, whether rooted in autonomy, rights, or dignity, must form the bedrock of any future agreement. The restoration of democratic freedoms and the inclusion of local voices are not just moral imperatives—they are strategic necessities.

The recent dialogue in Delhi may not have made headlines, but it deserves notice. In a region where silence has too often signalled escalation, even tentative conversation is a welcome shift. But to build real peace, we must go further. Symbolism must give way to structure. Rhetoric must yield to realism. And Kashmiris must be moved from the margins to the centre of the conversation.

Only then can the subcontinent hope to break free of the cycles of mistrust, conflict, and missed opportunity that have defined its modern history.

Have you liked the news article?