Despite countless obstacles and relentless challenges, Muslims in India have, over the past century, not only founded institutions of global repute but also sustained them with vitality and purpose, even amid severe shortages of resources.

Aligarh Muslim University, Jamia Millia Islamia, Darul Uloom Deoband, Mazahir Uloom Saharanpur, and Nadwatul Ulama in Lucknow are all part of this historical continuum. These institutions did not merely illuminate the subcontinent; they spread intellectual light far beyond it.

A relatively new yet exceptional link in this luminous tradition is the Institute of Objective Studies (IOS). Set up in 1986, the IOS has pioneered a disciplined effort to understand and address the social, educational, economic, and intellectual challenges faced by Muslims not through emotive rhetoric, but through rigorous research and data-driven inquiry.

For any scholar researching Indian Muslims, or any journalist seeking serious material on the subject, the institute tucked away in Zakir Nagar, Okhla, in south Delhi, is the first and only destination.

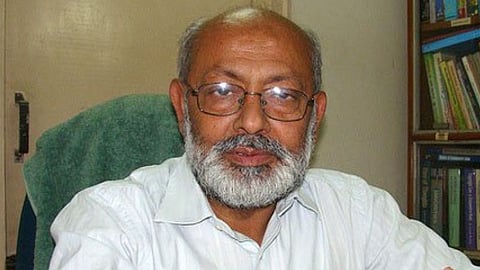

On January 13, a painful piece of news arrived from Delhi that Dr Mohammad Manzoor Alam, the institute’s founder, guiding spirit, and intellectual architect, passed away at the age of 80.

His death marked not just the loss of an individual, but the end of an entire era.

In my own life, Dr Manzoor Alam’s role went far beyond that of an institutional head or intellectual mentor. In the early 1990s, after graduating from Government College in the small town of Sopore, I came straight to Delhi to study journalism. It was in fact my first journey outside Kashmir. My uncle, who lives in the United States, gave me Dr Alam’s number for any eventuality.

Admission was secured, but accommodation was not. Carrying that worry, I went to the Vateg Building in Nizamuddin West locality, where I met Dr Alam for the first time. He arranged a place for me in the Mumtaz Building above Bharat Offset Press in Gali Qasim Jan in Old Delhi, where I stayed for the next four months, till I got a feel of Delhi roads, life, and transport. I still remember that he signed my admission form as my local guardian.

He also introduced me to Maqbool Ahmad Siraj and, in effect, entrusted me to him. Siraj had left a senior position at a reputed English national daily and moved from Bengaluru to Delhi to co-found a feature agency, Feature and News Alliance (FANA), with Dr Alam.

The mentorship, guidance, and quiet care of these two men shaped not only my understanding of journalism but also taught me how to view the collective concerns of society through a wider lens without an emotional taint.

Building Platforms

As the noted scholar and historian Professor Zafar Ahmad Nizami once observed, Dr Alam’s greatest achievement lay in bringing together English-educated Muslim professionals and intellectuals on a single platform and engaging them on issues affecting the wider Muslim community.

Whether it was a former chief justice of the Supreme Court, eminent legal scholars, or leading researchers, Dr Alam had a rare ability to assemble diverse minds and channel their expertise into serious academic work. One of his major achievements was coordinating historians to produce a three-volume work on the role of Muslims in India’s freedom movement.

Born in 1945 in the remote village of Ranipur in Bihar’s Madhubani district, Dr Manzoor Alam pursued higher studies in economics at Aligarh Muslim University and completed his PhD. He went on to serve as an economic adviser in Saudi Arabia’s Ministry of Finance. It was a comfortable life, but the intellectual and collective condition of Indian Muslims would not let him rest easy.

His return to India was not merely geographical. It marked the beginning of a far larger intellectual and practical project.

While IOS brought together English-educated scholars, Dr Alam also felt the need for a similar platform for religious scholars. Along with Qazi Mujahidul Islam Qasmi and Maulana Amin Usmani, he helped establish the Islamic Fiqh Academy.

The academy produced pioneering research on contemporary issues faced by Muslims. It was not just a juristic council but a forum that brought together scholars from different schools of thought, disciplines, and intellectual backgrounds to seek serious, non-emotional, and contextually relevant solutions.

Its standing became evident after the end of apartheid in South Africa. When Nelson Mandela assumed power in 1994 and began framing a new constitution and legal order, his government did not turn to Saudi Arabia, Iran, or Pakistan for guidance on Muslim personal law. Instead, it looked to the Islamic Fiqh Academy in New Delhi’s Zakir Nagar.

The reasoning was simple yet profound: an Islamic institution functioning within India’s multi-religious, multi-ethnic society was better placed to understand the needs of Muslims in a similarly diverse South African context. The choice was not only a vote of confidence in the institution but an international recognition of the intellectual maturity of Dr Manzoor Alam and his colleagues.

Dr Alam was also deeply conscious of the power of media as a tool for empowerment. With a few associates, he set up the United Mass Media Association (UMMA), aimed at providing scholarships to journalism and mass communication students and helping them enter mainstream media.

Under this initiative, the Feature and News Alliance was launched in Delhi under Maqbool Ahmad Siraj, along with a documentation centre. After completing my journalism studies, I worked at FANA for four years before moving to national media.

While most of Dr Alam’s institutions flourished, FANA was the lone exception. After nine years, it had to shut down. This was even though its content appeared regularly in more than 150 newspapers. Had institutional support continued, it could have evolved into a remarkable experiment.

For young journalists, it functioned as a launch pad. Assignments were completed, scripts were refined with editors, and bylines appeared in leading newspapers. Translated versions were also circulated to Urdu and Hindi dailies. The report would become a household name in even remote corners.

Many journalists trained there continue to work in leading media organisations today. The documentation centre, which is a treasure trove, still functions in Zakir Nagar. Digitising it and making it accessible online to researchers and journalists worldwide is now an urgent need.

Documentation for Sachar Committee

When the Congress-led government set up the Justice Rajinder Sachar Committee in 2004 to study the social and economic status of Muslims, data compiled by the Institute of Objective Studies proved invaluable.

To him, tradition and modernity were not opposites but complements. As A.U. Asif writes in his biography, Dr. Manzoor Alam: An Untold Story of Justice, Inclusion and Equality, this balance made him a far-sighted thinker, neither trapped in nostalgia nor swept away by unrestrained modernism.

Since its founding in 1986, the IOS has organised more than 1,350 seminars and conferences, including 14 large-scale international gatherings. Its scholars have completed 475 research projects, an extraordinary achievement for a non-government institution.

These studies were not academic exercises alone. They aimed to understand ground realities and provide usable material for policymaking across education, economics, sociology, psychology, law, politics, minority rights, and media.

As Abdul Mannan, a former FANA colleague and now editor of a government journal, once remarked, Dr Alam knew how to work with both elephants and ants. He could seat senior judges, professors, bureaucrats, and policymakers at one table, while also involving grassroots workers, young researchers, and students in the same process.

Sustaining such an institutional ecosystem required resources, a constant challenge. Rather than relying solely on donations, Dr Alam pursued self-reliance. Under his supervision, Bharat Offset Press was set up in Old Delhi and continues to operate today, supporting the institute’s publishing needs. He also established two leading publishing houses, Qazi Publishers and Distributors, and Genuine Publications and Media Pvt. Ltd.

Another pillar of IOS is its research and reference library, housing around 14,000 books in English, Urdu, Hindi, and Arabic. Managed from the outset by Saad Niazi, the library’s organisation and professionalism are evident to anyone who visits.

Among Dr Alam’s other major initiatives was the creation of the All India Milli Council, to bring together leading scholars, clerics, and experts across disciplines. Its aim was to build consensus on community and political issues and avoid unnecessary divisions.

Dr Alam was not a leader who sought solutions through constant complaint or reactive protest. He consciously rejected grievance politics, choosing the harder path of intellectual formation, institution-building, and long-term planning instead. Nations, he believed, are built not by slogans but by knowledge, research, institutions, and sustained effort.

That conviction gave rise to IOS, the Islamic Fiqh Academy, the All India Milli Council, UMMA, publishing ventures, and research projects. Though they appear separate, they are links in a single intellectual chain, aimed at moving Muslims from emotional reaction to conscious, organised collective action.

End of Era

When Dr Alam trusted people, he gave them autonomy. He did not micromanage daily affairs. He built institutions, then allowed others to run them.

His passing marks the end of an era, but it also leaves behind questions.

Will these institutions remain mere memorials, or will they be renewed for a new age? Will IOS confine itself to seminars and reports, or evolve into a digital hub producing data, policy briefs, and wider public dialogue? Will an initiative like FANA be revived to help a new generation enter mainstream media?

These questions are part of his intellectual legacy. Those who inherit his work have a responsibility to nurture the seeds he planted.

His life offers a clear lesson: even with limited resources, adverse conditions, and constant resistance, institutions can be built and lasting marks left behind if vision is clear, intent sincere, and perseverance unwavering.

He is gone, but the institutions he founded, the ideas he shaped, the people he mentored, and the thought he cultivated endure. This is not an obituary of a man alone, but a record of an intellectual journey, one that began in deprivation and reached institution-building, research, dialogue, and global trust.

That is the true measure of Dr Mohammad Manzoor Alam, and that is his greatest legacy.

Have you liked the news article?