For much of the past decade, India placed its bets on a grand alignment with the United States, hoping to safeguard Western interests in the Asia-Pacific while counterbalancing China’s rise. That strategy has now reached its limits. A sudden chill from Washington DC has compelled New Delhi to take a sharp turn in its foreign policy. Once again, India reached out to Beijing, looking to stabilise borders and avert conflict. The shift comes at a time when US President Donald Trump spares no opportunity to wound Prime Minister Narendra Modi politically.

Trump’s latest move underlined this discomfort: appointing Sergei Gore as US ambassador to India. This may be a cause for celebration that Trump chose such a close confidante to represent him in New Delhi. But he also designated him as special envoy for South and Central Asia. The dual role ties India’s foreign policy back to Pakistan and Afghanistan—a linkage successive Indian governments have long resisted.

Gore’s constant shuttling between Delhi and Islamabad will amount to an American mediation in South Asia, precisely what India has publicly rejected. Trump has made it plain: Gore will push his agenda in the region.

This comes atop rebukes from Europe and the wider West, which accused India of profiteering by buying Russian crude, refining it, and selling it at higher rates in global markets. These combined pressures have forced India’s foreign ministry to seek a thaw with China after five years of frosty silence, dating back to the deadly Galwan Valley clash in June 2020.

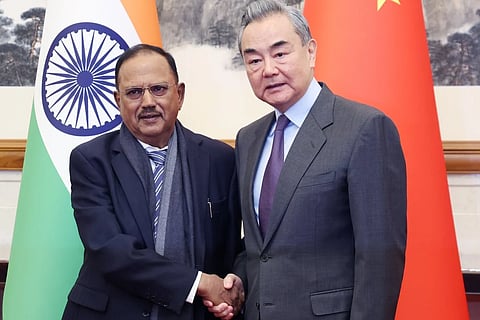

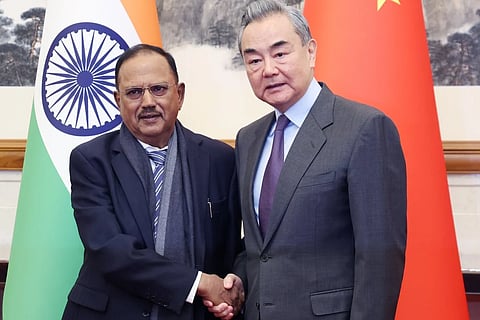

Ahead of Prime Minister Narendra Modi attending the 25th Summit of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) in Tianjin, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi paid an official visit to India on August 18-19. Earlier, Foreign Minister S. Jaishankar and National Security Adviser Ajit Doval undertook quiet missions to Beijing. The two sides discussed restoring travel and trade links, reworking border protocols, and preparing for Modi’s visit to Tianjin.

Experts on China affairs in Delhi say that the Chinese leadership is counselling Modi to ensure peace in the region and thereby normalise ties with Pakistan, avoid conflict and thus reduce openings for any American interference. For its part, Beijing prefers to keep the Himalayan front calm while it focuses on Washington and Taiwan.

Pattern of “Talks For The Sake Of Talks”

India’s diplomatic style, however, often frustrates its counterparts. Whether in Kashmir with Sheikh Abdullah, Mizoram with Laldenga, or Punjab with the Akalis, India has perfected the tactic of endless negotiations—wearing rivals down until disputes fade. The same approach has long been applied to border talks with China.

Trump himself fell victim to this pattern. During his first presidency, he pressed New Delhi over tariffs and trade imbalances. The response from New Delhi was to appoint negotiators. Yet Indian negotiators, led by then Commerce Minister Suresh Prabhu, would repeatedly visit Washington and hold several rounds of talks with US Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin. Prabhu would defer decisions, citing the need to consult political leadership. Munuchin recently said that when back in New Delhi, Prabhu would not pick up his calls for weeks, till announcing that he is again returning to Washington for the next round of talks. Trump’s first four years were effectively consumed by these talks after talks.

Biden, prioritising India as a counterweight to China, did not press for trade talks despite frustrations. But Trump, a transactional businessman keen on legacy, signalled to Modi in February that talks need to come to some conclusion. He wanted results—especially on correcting a trade balance.

Evidence of drift surfaced quickly. At a March briefing on the US-India strategic partnership at Capitol Hill, only 11 of 435 lawmakers attended—the lowest turnout since the India caucus was founded in 1993. For seasoned watchers, the signal was clear: interest in the relationship was waning.

China had earlier voiced similar complaints. In the late 1980s, Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi’s outreach to Beijing had established Joint Working Groups (JWGs), and Narsimha Rao’s government in 1993 formalised peace protocols: unarmed patrols, advance notifications, and bans on new infrastructure. Yet progress stagnated.

By 2003, China demanded an elevation of talks to higher levels. Thus, was born the mechanism of special representatives, typically India’s National Security Adviser (NSA) and China’s senior foreign policy envoy, to ensure an early resolution.

Fifty rounds of such talks have been held. Former NSA Shivshankar Menon recalls crafting a “give and take” framework with Chinese counterpart Dai Bingguo, under which India would drop its claim to Aksai Chin in Ladakh and China would relinquish its claim to Arunachal Pradesh. Smaller disputes would be resolved sector by sector. Dai even published the idea after retirement. But India never responded, preferring to keep the ritual of annual meetings alive.

In 2016, when I was part of a four-member Indian media delegation that visited Tibet and Beijing, Chinese officials bluntly told us that they had no interest in negotiations without progress. Shortly thereafter, border clashes intensified.

Latest Reset

During Wang Yi’s August visit, both sides agreed to revive special representative talks, form technical groups, and create fresh mechanisms for disputes in the eastern and middle sectors. Pilgrimages to Kailash Mansarovar will resume, direct flights will restart, and trade posts at Lipulekh, Shipki La, and Nathu La will reopen. China pledged to ease restrictions on rare earths, fertilisers, and tunnelling machinery. It also promised emergency hydrological data on rivers like the Brahmaputra.

Beijing claimed Jaishankar reaffirmed the “One China” policy in private, saying Taiwan is part of China. Delhi later issued a carefully worded clarification: it recognises “One China” but maintains economic, cultural, and technological ties with Taiwan. Beijing bristled at this backtracking, insisting no public clarification was needed after Jaishankar’s closed-door assurance.

Strategically, Beijing wants quiet borders while preparing for a possible confrontation with the US in the Pacific. Yet it views Delhi as playing a double game under American influence. India, too, has realised that over-reliance on Washington is risky, especially after Trump gutted the Trans-Pacific Partnership and showed no interest in Asia-Pacific security frameworks.

Meanwhile, economic realities loom large. India’s trade deficit with China in FY 2024–25 hit $99.2 billion, driven by dependence on electronics, batteries, and chemicals. Neither side has abandoned disputes, but both acknowledge that conflict serves no purpose. “The obstacles of recent years were not in our interests,” Wang Yi admitted.

Senior analyst Bharat Bhushan says the dream of greatness through US support has left Delhi adrift. He argues that political leaders mistake blind loyalty for strategy. Trump’s trade penalties have already driven Indian ministers back toward Moscow and Beijing—moves marketed as “strategic nimbleness,” but perceived by others as weakness. Yesterday’s calls for boycotts of Chinese goods have given way to partnerships.

Sources in Delhi claim that Wang Yi, during his visit, has offered to finalise the Sikkim sector based on the 1890 treaty with the Qing dynasty. The other sector will follow later. In the past, India has resisted such a proposal, fearing it would embolden Beijing to consolidate gains in Bhutan’s Doklam plateau. Analysts warn this could bring China closer to the Jampheri Ridge, threatening India’s narrow Siliguri Corridor, the lifeline to its northeast.

Despite resistance, during Wang’s visit, India agreed to form an expert group under the Working Mechanism for Consultation and Coordination to explore this option. Beijing declared that a “new consensus” had been reached to begin negotiations in favourable sectors.

Wang Yi himself is regarded in the West as the “Silver Fox”—a patient tactician who uses calm tones and bureaucratic persistence to tire opponents until they yield. Behind his soft delivery lies decades of experience and a reputation for being firm and unyielding. His favourite maxim sums it up: “Beijing’s way is to speak softly while holding firm.” He often adds, “When we say something twice, it means we will act on it twice.”

India today stands between two hard truths: a powerful neighbour and a United States led by a President unwilling to indulge in delay. For New Delhi, the choice is stark. It can either continue drifting between great powers or confront its own contradictions and craft a foreign policy rooted not in wishful alignments but in hard regional realities.

Have you liked the news article?