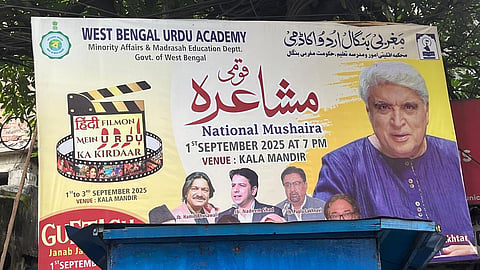

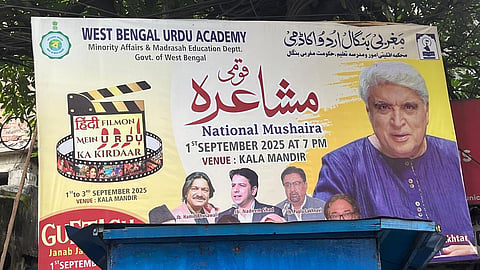

Javed Akhtar’s recent ‘exile’ from the West Bengal Urdu Academy event did more than generate headlines. It dwarfed a bigger debate about Urdu in Hindi cinema, which was the event’s main theme. The media precipitately reduced the whole issue to the conflict between the lyricist and the Urdu Academy. The controversy carried a tinge of ‘Muslim fundamentalism,’ reflecting today’s cultural and political ideologemes. However, the discussion on Bollywood’s uneven relationship with Urdu was lost in the sound and fury of cultural climate of the country. Et tu, Brutus?’ finds a new stage – ‘Et tu, Bollywood?’ You speak against the very world that gives you voice.

While luminaries like Akhtar and Naseeruddin Shah generally speak against the ill-treatment meted out to Urdu, their voices become muted on the marginalization of Urdu both within the film industry and beyond. The real exile of Javed Akhtar and the Platonic exile of Urdu have much to negotiate with, in the largest film industry of India. Forget Javed Akhtar. Just ask an ordinary speaker of Urdu. How s/he feels when Urdu is made to fall within the category of ‘Hindi cinema,’ which merely invokes Urdu as a ghost language of Hindi. Ghost because it remains invisible even when it gives a decorative splash to Hindi.

On the other hand, Bollywood has its own problem of mating language with geography. It is a more sinister design than the imaginary seduction of Derrida in which regionally anchored categories of Tamil, Punjabi, Telugu and Bengali cinema still find release. By blurring the distinction between language and geography, Bollywood naturalizes ‘Hindi’ both as a lingua franca and a national marker.

Bollywood crafts a nifty seduction, from the ticket counters to the posters written in Devanagari, to the censor board’s approval, each film is promoted as ‘Hindi cinema.’ Urdu is unswervingly shown as the obliging lover in the background of this vellicating gyration. Despite flirting with its rhythm, poetry, emotions, Urdu is never welcomed to the marquee. This is pure power play – with a grand nationalistic foreplay. By calling itself ‘Hindi cinema,’ Bollywood does more than just market films. It positions Hindi as the major language of desire, relegating Urdu to a seductive supporting role and quietly eroding the Hindustani fusion that once united them in a perfervid cuddle.

The West Bengal controversy thus dramatized a pattern that has long been normalized. Urdu is tolerated as lyricism but disowned as identity. Some Urdu writers might be celebrated when it suits the moment, but the language itself is still treated as suspect. It is pushed to the margins, is painted as foreign and is even branded dangerous. That’s why the headlines about Javed Akhtar’s ouster tell only half the story. The bigger question wasn’t about one poet being banished but about how Bollywood and the larger film industry quietly encode which languages and which communities get to belong at the heart of ‘Hindi cinema.’

The irony, of course, is that the heartbeat of Bollywood has never really been Hindi at all. It’s Urdu. The songs we hum, the dialogues we remember, the inflections of love and heartbreak that define the industry have all drawn their power from Urdu. The very vocabulary of romance, anger, hatred, inebriation such as Ishq, Junoon, Inteqam, Bekhudi are unambiguously Urdu.

And yet Urdu disappears like a Shakespearean wraith, alluring in absence and menacing in presence. Such is the sensuous grip of politics.

Since independence, Bollywood has served as a cultural sylph for the country, reproducing an image of ‘India’ for mass consumption. Certain festivals such as Holi, Diwali, Karva Chauth shimmer like enticing temptations while festivals like Onam and Bihu are out of its perimeters. The same is true of the language. The nuanced flavours of Awadhi, Bhojpuri, Braj, Khadi Boli, Maithili, and innumerable other languages spoken by about half of the population are mixed with Hindi, which is presented as the country’s cinematic vernacular. This silent effacing is way too powerful. Even my mother tongue, Bhojpuri, flows through me like a recollection of a touch I cannot fully claim. Not because I’m ashamed, but because Hindi’s supremacy and the discourse of mutual intelligibility leave little space in my daily encounters.

Aijaz Ahmed, the cultural theorist put it so succinctly – the very notion of ‘Indian literature’ is disingenuous, since no single language or region can stand in for the whole. Yes, he was talking about the category of ‘Indian literature’ but it stands equally for the glossy frame of Bollywood. After all, to read literature needs literary prowess but to see requires not even the category of ‘ways of seeing.’ Bollywood sells itself as a national cinema but it, in reality, it is the ‘North’ which is repackaged as ‘India.’ In this repackaging, Urdu is not even accorded the courtesy of a hyphen.

Bollywood spoke a language infused with Urdu from the first echoes of sound on celluloid. It was fluid, melodic and incredibly rich. However, when regional and religious politics became more prevalent, the industry became more cautious when it came to creating its own language. It shifted into something more subdued instead, referring to it as Hindustani, a name that sounded of denial and longing yet promised detachment. This imagined register, which could simultaneously pass for everyone’s and no one’s, flirted with inclusivity by assuming the common tongue of a fragmented population. However, Hindustani was never innocent. The goal of the well-planned seduction, a political endeavour disguised as linguistic harmony, was to soften the harsh edges of the Hindi-Urdu conflict, which by the 1930s had started to sound like the heartbeat of a country splitting in two. And this delicate deception found the ideal stage in cinema, which was eventually waiting like a devouring lover.

For instance, the first talkie, Alam Ara (1931), spoke in a language of desire, a liminal language that glided like silk. What the audience heard as ‘Hindustani’ was not a neutral language. It allowed filmmakers to enjoy Urdu’s elegance, while assuaging the phobias of Hindi nationalists. A quiet imbalance existed behind the façade of harmony. Urdu served as the muse, yet Hindi bore the signature. After Independence, the delicate dance faltered. With Hindi enthroned as the ‘unofficial national language,’ Hindustani lost its charm, and Urdu, formerly the lover’s tongue of cinema, was left to haunt its outskirts, shivering just beyond the light.

Madhava Prasad, a film historian, offers a different optic to understand Bollywood’s covert linguistic gyration – ‘structural bilingualism.’ Bollywood, he claims, has always been flirtatiously bilingual by design. This enticing duality revealed itself in its early decades as Hindi and Urdu intermingled, giving rise to the sensuous hybrid known as ‘Hindustani.’ However, now the global gaze via cultural economy necessitates a new pairing: Hindi and English. This is reflected in film titles with cosmopolitan allure, such as War, Super 30, Ghost Stories, Diplomat, Blackout, Skyforce, and The Accidental Prime Minister, all of which promise a reach beyond borders. However, beneath this exquisiteness, lies an indescribable tension- the tension of Hindi having sway. But which Hindi? An unsmiling, Sanskritized Hindi of nationalist discourse or ‘Urdu-inflected Hindi’ that once gave fodder to Bollywood?

Bollywood’s language politics become especially revealing in historical films. In Sohrab Modi’s Sikandar (1941), both Alexander and King Porus spoke in Urdu, reflecting the polyphony of pre-independence India. But by the 1960s, things changed. In Sikandar-e-Azam (1965) or Changez Khan (1957), the so-called invaders suddenly spoke Urdu, while Indian kings responded in Sanskritised Hindi. The linguistic division carried a clear ideological message. Hindi was the language of the nation. Urdu became the language of outsiders. This was not simply cinematic choice – it echoed the nationalist rewriting of history itself, where figures like Porus were recast as proto-national heroes, while Urdu was made to stand in for foreignness.

Even as we debate over the marginalisation of Urdu, the tongue itself hasn’t truly vanished from Bollywood. Industry insiders whisper that Urdu graces dialogues and songs, accounting for 70% to 90%. Without the dulcet cadence of Urdu, the biggest blockbusters would be but a dream unformed. Yet, the industry acknowledges not this debt. The music of Urdu resounds in every corner, yet its honoured name lies hidden.

In recent years, Urdu, like its people, has become the usual suspect. This whispered stigma reflects a larger cultural mystery, one that connects Urdu to Muslim identity and hints at betrayal. Meanwhile, English, another ‘foreign’ language, basks in cosmopolitan splendour. The contrast is scrumptiously ironic. The ‘colonial’ language conquers; the anti-colonial vernacular is not even the conquest.

Bollywood’s timestamp with language is nothing but the pirouette of dominance. Lyrics and dialogues are mere cultural seduction that expose the private politics of India’s creative imagination. Under the guise of ‘Hindi cinema,’ individuals like Javed Akhtar, create the seductive appearance of being ‘Hindustani,’ but refrain from publicly acknowledging Urdu as Bollywood’s pulse. Given this, West Bengal’s event on ‘Urdu in Hindi cinema’ is more than just a debate; it’s a swirling dance of language, faith and nation with identity and power becoming what Walter Benjamin calls ‘the phantasmagorical culture of commodity’, with a seductive power over the people.

(Courtesy: Kafila Online)

Have you liked the news article?