A huge platoon of YouTubers has sprung up, eager to make quick bucks by commercializing Kashmir’s history. Most of these self-styled YouTube “historians” are non-professionals who have hardly studied history beyond the matric level.

Lacking depth and scholarly discipline, they produce shallow, sensational narratives designed purely for entertainment and monetary gain. To expand their viewership, they mix fact with masala, adding salt and spice to make history juicy, dramatic, and politically useful.

Lately, the Sher and Bakra narrative has become one of their favourite themes, often presented with distortions and half-truths to keep audiences hooked.

One such distortion, endlessly repeated, claims that the term Bakra arose because the followers of Mirwaiz Maulvi Yusuf Shah wore long beards, like goats. This is sheer fallacy, is historically inaccurate, and deeply demeaning, as it equates the sacred beard, a symbol of faith, with a goat’s bleat. To prevent such falsehoods from taking root in our collective memory, I feel compelled to set the record straight.

Kashmiris rarely call people by their formal name. Ghulam Mohammad becomes Gula, Ghulam Nabi turns into Naba, Ghulam Rasool is Rasul or Lassa, Khadija becomes Khaje, Zanab becomes Zaena, and Mehr-un-Nisa is simply Mehre.

Beyond these affectionate diminutives lie sharper names born of satire and mockery, revealing a person’s character, behaviour, and physical stature: Qadir Nata (fatty Qadir), Shaitan Waza (the devilish cook), Naber Nunwoar (barefooted Naber).

Such nicknames are cultural verdicts, judgments pinned on people like permanent badges. They combine humour and critique, reflecting how ordinary Kashmiris interpret and classify their world.

When trade unionism in 1924 and modern politics in the 1930s entered the Valley, this old tradition flowed naturally into the new arena in its pristine form, finding expression through plays, radio features, and later television episodes. Among such serials, Mochama is still fondly remembered. Leaders and movements were reimagined through metaphor, making complex struggles accessible to the subaltern masses.

From Kalhana to Hamid Ullah Shahbadi

This instinct for metaphorical naming has deep historical roots. In the twelfth century, Kalhana, in his monumental Rajatarangini, freely bestowed epithets on kings and queens. His nicknames were not casual labels; they were carefully chosen symbols of irony, praise, or condemnation.

Queen Didda, formidable yet ruthless, was called Charanhina and Diddakeshma—“Didda the Limping One” and “Witch.” These names reflected her physical deformity, cunning, and unyielding grip on power. Through such metaphors, Kalhana rendered judgments on rulers he could not openly criticize, offering the people a coded language to speak about their masters under the heavy shadow of feudal authority.

This tradition continued through medieval times, becoming a subtle weapon for the subaltern masses to challenge their oppressors without open revolt.

Centuries later, Hamid Ullah Shahbadi wielded satire against Sikh rulers and officials. His biting epithets became legendary: Kazib Rather for a deceitful qanungo, Adawat Kaul for a vindictive patwari, Fasad Bhat for a quarrelsome harkara, Rishwat Baba for a bribe-hungry qazee, and Chugli Baba for a conniving informer or news reporter.

Each name was a miniature portrait, stripping authority of its grandeur, demeaning its functioning and exposing its corruption. These were more than jokes; they were weapons of silent protest. In Kashmiri society, where dissent invited punishment, nicknames became a hidden transcript, a secret language through which the powerless mocked power and preserved their dignity.

Language of the Powerless

Nicknames thrive in unequal societies. A tyrant might be likened to a wolf, a greedy landlord to a vulture, a corrupt courtier to a crow. These images captured truths too dangerous to speak aloud.

In Kashmir, where centuries of foreign rule suppressed open protest, this culture of coded speech flourished. When political awakening swept through the Valley in the 1930s and 1940s, these old symbols found new political meaning. Once again, animals became metaphors, this time for rival ideologies.

The Lion Roars

Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah’s rise was like a storm. Towering, eloquent, and fearless, he electrified a humiliated people. They named him Sher-e-Kashmir—the Lion of Kashmir.

The lion symbolized majesty and defiance. Abdullah carefully cultivated this image. Stories spread of miraculous leaves inscribed with the words: Pane wethrun key ah che shooban Sher-e-Kashmir zendabad (This leaf bears testimony: Long live the Lion of Kashmir!). Many believed this to be a divine endorsement of his mission.

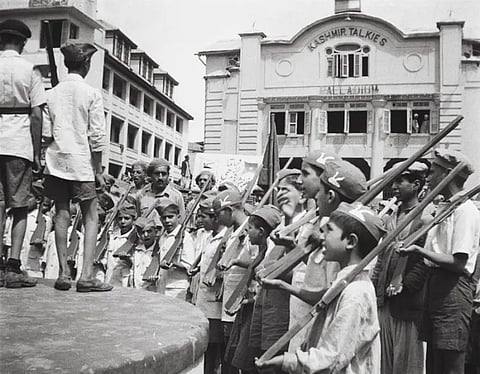

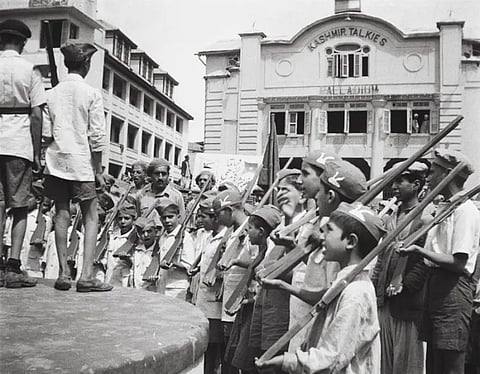

His followers proudly called themselves Shers, warriors of the Lion, defenders of Kashmiri identity and dignity against Dogra feudalism and imperial interference.

The Goat Bleats

Opposing Abdullah’s National Conference was the Muslim Conference, led by Chowdhury Ghulam Abbas and later Moulvi Yusuf Shah. Their politics were framed in religious terms and aligned with Pakistan.

It was amid this rivalry that the counter-image of Bakra, the goat, emerged. Contrary to later claims, it did not arise from Yusuf Shah’s followers wearing long beards.

In Kashmiri culture, the goat carried layered symbolism: gentle, easily led, and ultimately destined for sacrifice at Eid. To call someone Bakra was to brand them passive instruments of outside forces; first the Dogra state, later Pakistan. It was both an insult and a prophecy of doom.

Street politics soon revolved around these animal symbols. Posters depicted roaring lions confronting trembling goats. Slogans rang out:

“Sher ke saath chalo, Bakron ko bhaga do!” (Walk with the Lion, drive away the Goats!).

From Quit Kashmir to 1947

During the Quit Kashmir movement of 1946, effigies of goats were mock-sacrificed in rallies to ridicule Abdullah’s opponents.

The following year, when tribal raiders swept into the Valley, the symbolism intensified:

• Shers were celebrated as defenders of the Valley and champions of accession to India, while the government of the day hailed the incoming army as “Tiorun Ababeel.”

• Bakras were vilified as collaborators of the raiders—“mujahideen,” the marauding “shepherds” who plundered the meadow and dishonoured its ethos.

The Sher–Bakra divide hardened into collective mythology, defining political loyalties for decades.

Echoes That Remain

Even after Sheikh Abdullah’s dismissal and arrest in 1953, the old nicknames endured. Cities and villages split into Sher mohallas and Bakra mohallas, their loyalties visible in flags, processions, songs, and slogans.

Though the terms have faded in modern politics, their echoes remain etched in memory. They remind us that language itself can be a battlefield.

By calling Abdullah a Sher, the people crowned him a king in their hearts. By branding his rivals Bakras, they condemned them to weakness and submission.

Long after the Lion’s roar faded and the Goat’s bleat fell silent, these words survive; proof that in Kashmir, as in all lands of struggle, naming is power, and nicknames are the subaltern’s poetry of resistance.

Even today, this tradition lives on through contemporary nicknames such as Soele Gernade, Toffee, Nike Mir, Gule Curfew, Farooq Disco, and Cricket Moulvi, showing how satire continues to capture the spirit of the times.

Have you liked the news article?