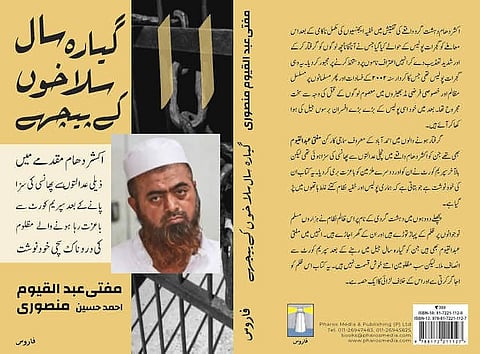

Book: Giyarah Saal Salaakhon Ke Peeche (Eleven Years Behind Bars)

Author: Mufti Abdul Qayyum Ahmad Husain Mansoori

Publisher: Pharos Media & Publishing Pvt Ltd, New Delhi, India

Year Of publication: 2022

Price: Rs 300 Pages: 239

ISBN: 9788172211127

Mufti Abdul Qayyum Ahmad Husain Mansoori’s Giyarah Saal Salaakhon Ke Peeche (Eleven Years Behind Bars), published by Pharos Media & Publishing Pvt. Ltd., New Delhi, is a piercing cry of truth from the depths of wrongful incarceration. The memoir recounts his eleven-year ordeal behind bars after being falsely implicated in the Akshardham attack case of 2002.

It is both a deeply personal story and an unflinching commentary on the state’s systemic bias, communal politics, and the abuse of legal and policing mechanisms against an already vulnerable community.

The book begins with his eventual release and acquittal, when the Supreme Court of India finally declared him and three others innocent, absolving them of all charges related to the Gujarat temple attack. This judicial relief, though monumental, could not erase the eleven years of torture, humiliation, and despair Mansoori endured.

The verdict, beyond proving his innocence, symbolised how truth in India’s judicial system often arrives too late, after lives have been shattered beyond repair. What emerges is a story not merely about individual suffering but about the failure of institutions that traded fairness for prejudice.

Mansoori’s arrest by the Ahmedabad Crime Branch marks the beginning of a systematic attempt to construct an enemy figure out of an innocent scholar. The police seemed less interested in finding the actual culprits and more determined to craft a narrative that would appease political expectations and reinforce a broader national myth of Muslim culpability.

Whipping Communal Hysteria

The author situates his ordeal within a wider historical pattern of cycles of communal riots and pogroms in which Muslims were the victims, after which the state’s energies were geared toward painting the community as perpetrators of terrorism. Scholars, imams, and educated youth became new targets, accused of extremism and anti-national activity. This transformation, Mansoori argues, was intended to disempower the Muslim community by delegitimising its most articulate representatives.

He names senior politicians, such as the then Home Minister Shivraj Patil, as bearing responsibility for the atmosphere of hysteria and persecution. Mansoori also notes the silence around others like P. Chidambaram, whose tenure later continued policies of securitisation that deepened the paranoia against Muslims.

Through this layering of names and institutions, the author exposes how communal ideology seeps across party lines, shaping state power in ways that transcend individual governments.

Torture Chambers and Forced Confession

The most terrifying parts of the memoir are those describing the torture chambers of the Ahmedabad Crime Branch. Mansoori lays bare the cruelty with both restraint and precision, narrating how he was beaten, electrocuted, deprived of sleep, and mentally broken to the brink of death.

In a desperate bid to survive, he signed a false confession. The illusion of legal procedure soon disintegrated into pure barbarity. Police officers like ACP Girish Kumar Lakshmibhai Singhal, and even a Muslim inspector, Ashraf Chouhan, whom Mansoori calls “worse than a Nazi,” played leading roles in his torture sessions. These officials treated human suffering as a performance for media headlines and political credibility.

Mansoori was not only coerced into confessing but also pressed to implicate others in the supposed conspiracy. He recalls how the police fabricated evidence and fed false information to the press, claiming that the accused had been legally arrested earlier, when in reality they had been held illegally for days in secret custody.

Judges, rather than acting as safeguards, routinely extended police remand without listening to the pleas of the prisoners. The climate of terror inside interrogation rooms ensured that no one dared to speak of the torture they endured. Fear replaced faith, and silence became the only defense.

The Kashmir ‘Connection’

His narrative then shifts to an unexpected episode when he was transported to Kashmir as part of the investigation. There, the local police reportedly realised that he had been falsely framed. In a brief but distinct contrast to his experience with the Gujarat police, the Jammu and Kashmir Police treated him more humanely, even allowing him some freedom of movement.

Yet the shadow of death followed him constantly. On several occasions, he was taken out under the pretext of transfer, fearing that he was being led to a fake encounter. The fear of being executed and “disappeared” haunts every page of his recollections.

One of the most striking elements of the case, according to the author, was the so-called discovery of letters from the slain attackers allegedly written by him. He dismantles this claim through sharp observation. The letters were found on the bodies of the attackers, yet they were miraculously clean, untouched by blood, bullets, or dirt. It was a clear sign that they had been fabricated later to build a case.

Such planted evidence reflects the depth of conspiracy within the system and the ease with which falsehood could be legalised.

Prison Hierarchies

Inside jail, Mansoori discovers another world governed by its own laws of hierarchy and survival. He paints a detailed portrait of prison society where wealth determines comfort even behind bars.

The rich inmates use money to buy privileges. The poor are often incarcerated for petty crimes born of poverty, and they resign themselves to endless suffering. Some had adapted so deeply to prison life that freedom itself frightened them. Returning to a world without means, jobs, or homes seemed worse than captivity. Amid this grim landscape, letters from family and occasional meetings become a prisoner’s lifeline, bridging the emotional distance between despair and hope.

Despite the dehumanising environment, Mansoori found sustenance in his faith. Praying, teaching, and maintaining religious discipline helped him preserve self-respect even in degradation. Ramadan in prison transformed into a time of quiet solidarity. Fasting, despite minimal facilities, becomes an act of defiance and spiritual assertion.

Islam, for Mansoori, did not merely offer comfort; it became his shield against total disintegration. Through his prayers, he learned to turn torture into testimony, to endure humiliation without surrendering his dignity.

Several passages reflected on the role of community solidarity in achieving justice. The Jamiat-e-Ulema-e-Hind and particularly the Arshad Madni group stood beside him when legal costs became unbearable, funding their appeal before the Supreme Court.

Without such institutional and community support, he notes, justice for the poor and marginalised remains impossible.

Yet the memoir never retreats into sentimentality. Mansoori recounts one Muslim jailor expressing displeasure at his release, exposing the deeper malaise of internalised prejudice and triumph of fear even within the community itself. His story becomes an allegory for the psychological fragmentation of Indian Muslims, worn down by both external oppression and internal mistrust.

The cost of imprisonment went far beyond personal pain. During his years behind bars, Mansoori lost his father and several close relatives. Their deaths, occurring while he remained falsely imprisoned, left scars deeper than the physical torture he endured. Even after his release, he continued to face bureaucratic discrimination.

The Unhealed Scars

His passport application was denied due to adverse police verification, proving how punishment continues long after acquittal. Freedom, he realised, does not automatically restore dignity.

When Mansoori finally stepped out of prison after more than a decade, the world had changed irreversibly. Witnessing the evolution of cities, communities, technologies, and relationships, he felt both liberated and estranged.

Amid these transformations, the state’s capacity for cruelty remains intact, against which the author uses memory as a tool of resistance. The book closes with a contemplative tone, balancing grief and faith. He refuses bitterness but demands accountability, arguing that only truth can reconcile a fractured society.

Through the voice of one man who lived the horrors of fabricated terror cases, the Giyarah Saal Salaakhon Ke Peeche illuminates a larger pattern of injustice directed toward India’s Muslim citizens. Mansoori’s prose, simple yet piercing, carries the weight of an entire community’s anguish. His story echoes the unrecorded tales of countless others trapped in similar circumstances, stripped of liberty and dignity for the sake of political theatre.

What makes the memoir most compelling is its refusal to descend into hatred. Though every page resonates with anger and grief, Mansoori’s faith transforms that sorrow into a call for moral reckoning. The book indicts not only individual officers or politicians but a culture of prejudice that corrodes the very foundations of justice. It challenges readers to confront uncomfortable truths about the weaponisation of law, the complicity of media, and the moral cost of indifference.

Have you liked the news article?