Kashmir, often hailed as "Peer Vear" or the land of saints, has been as much a haven for poets as for mystics. Its ethereal landscapes, steeped in Sufi philosophy and romance, have long stirred the imaginations of wordsmiths.

Among its luminous literary figures, two names echo across the centuries: Rasul Mir (1840–1870), the lyrical lover known as the "John Keats of Kashmir," and Mehmood Gami (1765–1855), the revered mystic dubbed the "Jami of Kashmir."

These two poets, separated by a generation yet spiritually entwined, channelled human longing and divine love through their words. While Rasul Mir painted passion with the delicacy of a rose petal, Mehmood Gami sculpted stories of sacred devotion in the enduring rhythms of Persian epic.

Born in the small town of Dooru Shahabad in Anantnag, Rasul Mir's life was as intense as it was brief. He fell in love with a Pandit girl, Kongi, during his childhood. When she was married off, the separation became the source of his lyrical anguish. His grief found voice in haunting ghazals like "Kongi Hav Ti Paan" (Kongi, My Love, I Am Dying for a Glimpse of You), echoing through moonlit meadows and snow-cloaked orchards.

Like Wordsworth, Mir found muse in nature.

His verses brim with floral imagery, glacial rivers, and the scent of almond blossoms. And like John Keats, whom he is often compared to, Mir died young—at 31—leaving behind a fragile yet formidable body of work: 75 authenticated poems, 110 ghazals, and debates over many more. His poetic voice was one of unabashed emotion and melodic lyricism, a blend of spontaneity and soul.

Legend holds that Mehmood Gami once encountered the young Rasul Mir and remarked, prophetically, "Ames chi jane margi hind karen"—this man is destined to die young. And so it was. He died at 31.

Prominent Kashmiri singers such as Shameema Dev Azad, Abdul Rashid Hafiz, Gulzar Ahmad Mir, Yawar Abdal, Tanveer Ali, Abhay Sopori, Funkaar Noor Mohammad, and even Bollywood's Asha Bhosle have rendered his verses. Her 1966 rendition for Radio Kashmir lent Mir's poetry a cross-cultural and pan-Indian resonance.

His line "Zooni chaani myani roozan, Yeli watnas wuchhem sapdum" (My nights are moonless, / When will I glimpse my homeland again?) encapsulates the pathos and beauty of his craft.

Mir's verse is sensuous, melodious, and unabashedly romantic. His legacy lies not just in poetry but in the emotional register he etched into the Kashmiri soul. Mir's poetry provides a cathartic lens into collective longing and heartbreak.

As a muqdam (village chieftain), Mir belonged to a family of landed aristocrats. Despite his social stature, his poetry spoke the universal language of love and heartbreak.

His words, imbued with nature's imagery, elevated romantic ghazal to the realm of the divine. Scholars continue to debate whether his ghazals reflect earthly or mystical love, yet it is this very ambiguity that makes his work so powerful.

Mehmood Gami: The Sufi Storyteller

Mehmood Gami, born in the remote village of Gam, hailed from humble beginnings. Raised amid Sufi shrines, his father a saint and he later on too, Gami absorbed spiritual traditions and wove them into intricate poetic narratives. His pen name, chosen to rhyme with Persian masters like Jami and Nizami, was both tribute and ambition.

Gami was a literary polymath, equally at ease with ghazals, vatsun, naat, and most notably, the Persian-inspired mathnavi. His celebrated works include Laila-Majnun, Yusuf-Zuleikha, Sheikh San’an, Qissa-i-Haroon Rashid, and Mansoor Nama. These tales were not mere retellings but spiritual allegories, exploring the soul's quest for divine union.

His devotion to Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) manifests in deeply spiritual verses such as:

Tchukh Aalman Badshah, Ya Abdul Qadira

Beydaad Gomut Tchum Setha, Ya Abdul Qadira.

(You are the king of all worlds, O Abdul Qadir! My pleas are not being resolved, O Abdul Qadir.)

Gami earned fame not only for his poetic depth but for his humility and accessibility. He became a spiritual guide, or "pir," for the community, offering counsel and comfort through both words and presence.

If Mir was the voice of human love, Mehmood Gami was the mystic chronicler of divine love.

He revolutionised Kashmiri literature by introducing structured Persian literary forms into the Kashmiri language. His mathnavis seamlessly blended the rhythmic sophistication of Persian poetry with the earthy directness of Kashmiri folk tradition.

His Yusuf-Zuleikha, in particular, is considered one of the foundational texts of Kashmiri literature, weaving religious motifs with romantic yearning in a way that speaks to all generations.

Two Voices, One Valley

If Mir was the poet of romantic yearning, Gami was the custodian of spiritual enlightenment. Mir's concise ghazals dripped with personal pain; Gami's epic mathnavis swept readers into mystical journeys. One whispered into a beloved's ear; the other sermonised from a Sufi pulpit.

Yet both deepened the literary consciousness of Kashmir. Mir's influence shaped the romantic traditions of later poets like Mahjoor, while Gami's Sufi legacy paved the way for mystic poets like Wahab Khar and Shamas Faqir. Their poetry bridged the human and the divine, the intimate and the universal.

Mir’s poetry, often spontaneous, teemed with metaphors, emotional imagery, and a romanticised nature. In contrast, Gami's poetry provided readers with expansive narratives filled with philosophical undertones, often seeking to educate the heart through allegory.

Dr Tariq Ahmad Bhat, a specialist in folklore and literature from the University of Kashmir, frames Gami as a "spiritual mapmaker," his mathnavis acting as "journeys into the soul." Of Mir, he says: “He gave the Kashmiri ghazal an unprecedented romantic fervour. His verses go beyond sentimentalism, representing a deep yearning for unity with the beloved, whether human or divine.”

Another Kashmiri literary critic, Tawseef Ahmad, adds, “Gami's introduction of Persian forms expanded the literary toolkit of Kashmiri writers. His Yusuf-Zuleikha is a textbook of structure, emotion, and spiritual symbolism. Rasul Mir, on the other hand, established the Kashmiri ghazal as a vessel for romantic idealism.”

Both poets, according to Ahmad, offer a mirror to the Kashmiri soul. “Rasul Mir’s poetry is emotional, fragile, and musical. Gami’s is sturdy, wise, and deeply philosophical. One clutches the heart; the other guides the spirit.”

Living Legacies: Mir Moudan and Gami’s Resting Place

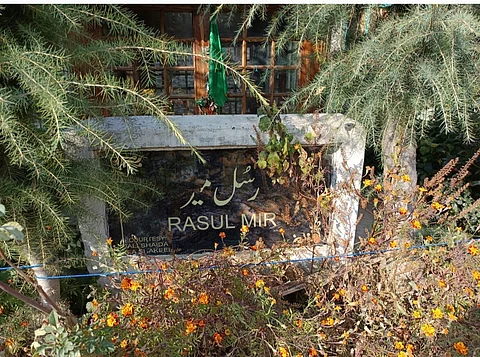

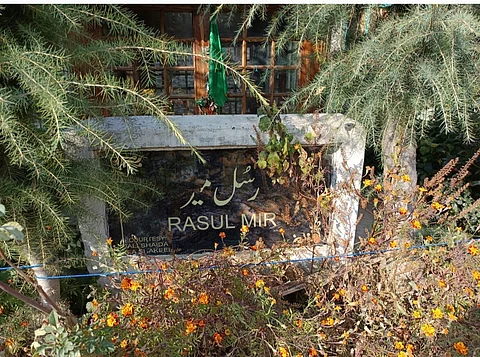

In Dooru Shahabad, Mir Moudan remains a sacred space.

It is here that Rasul Mir once sat weaving verses, where he allegedly experienced a dream of Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) that transformed his spiritual trajectory.

At Mir Moudan, where Rusul Mir lived beside Khanqah Faiz Panah mosque, the poet would sit and weave verses while giving predictions. Ahad, an 80-year-old caretaker who has tended the shrine for thirty years, explains that Mir used to share poetic insights and mystical predictions in that ground.

“After that vision,” says Ahad, “his poetry took on a different hue. It wasn’t just love for Kongi anymore; it was love for something eternal.”

"This place is deeply pious," Ahad notes. "Three luminous saints—Hazrat Amir Kabir, Shah Hamdan, and Sheikh ul-Alam—worshipped here before Rusul Mir."

Mir was laid to rest beside the shrine of Mir Mohammad Hamadani, near the mosque he frequented. Today, the community gathers here every 6th day of the Islamic calendar, with 10-12 families sharing the duty of maintaining the shrine and traditions. Prayers, Naat recitations, and storytelling continue until sunset, connecting generations to Mir’s spiritual heritage.

Similarly, the grave of Mehmood Gami remains a pilgrimage site. Local resident Habibullah Ahmad describes it as a haven of peace: “Just sitting there, you feel enveloped by his presence. His wisdom lingers in the air.”

Cultural Resonance

For the people of Kashmir, these poets are not relics but living voices. Their verses are sung at Sufi festivals, taught in schools, recited at weddings, and whispered in moments of solitude.

Aasif Rashid, a young student, says, “When I feel lost, I remember lines from Mir or Gami. They are like stars guiding me back to myself. Their words are lullabies, prayers, and poetry all in one.”

Visitors from Srinagar, Baramulla, and beyond make their way to these shrines, finding solace in sacred spaces shaped by verse. For them, poetry becomes a pilgrimage.

In a region often marked by socio-political complexities, the verses of Rasul Mir and Mehmood Gami offer a language of continuity and hope. They preserved not only a literary tradition but a way of seeing the world—one that honours love, spirituality, and cultural memory.

Their legacy is not confined to academia or oral tradition. It lives in the soil of Kashmir, in the voices of singers, the hearts of devotees, and the pages of every young poet trying to make sense of longing and belonging.

In their poetry, Kashmir found a mirror, a map, and a muse; thus, their words endure.

Have you liked the news article?