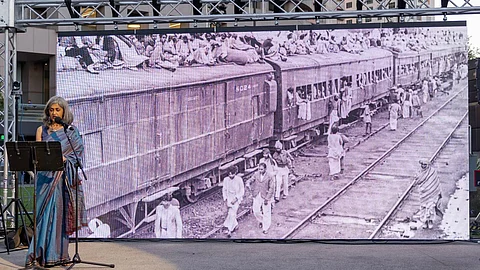

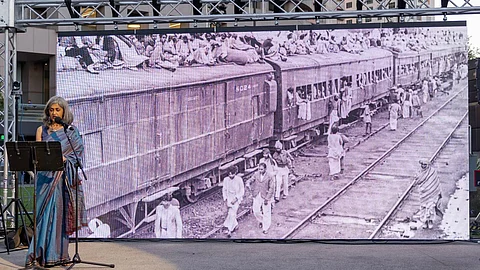

“You ask me why we still write about Partition — the gash that cuts our back, our arms, our spines pulsate from the tear…,” Sehba Sarwar reads aloud, her eyes lowered toward the lectern holding her poem “Partition” at the Grand Performances stage in the Grand Avenue Arts District of downtown Los Angeles.

A cacophony of confused, rushed, and anxious voices on a video playing in the background, disrupting the restrained cadence of her poetry, the low rustle of the paper she flips, and her jingling bangles. These are voices of the displaced, the migratory, the restless. These are voices of the past to which the black and white photographs zooming in and out on the stage backdrop belong.

These voices also infiltrate the present in which Sehba Sarwar locates herself, a transnational writer and activist who moves between Karachi, Houston, and LA.

Last year, she was designated co-Poet Laureate of the Altadena Library District, along with poet-activist Lester Graves Lennon. This July, the American Academy of Poetry honoured both with Poet Laureate Fellowships, enabling them to launch a poetry initiative titled “After the Fires: Healing from Histories”. The project seeks to provide space for the Altadena and Pasadena community to document history, and heal from the devastation of the 2025 Eaton Fires.

Sehba Sarwar’s writing and activism is marked by her refusal to shut out the past, compartmentalize the then and now, the here and there. As a 2024 City of Los Angeles Individual Artist Fellow, her reading at Grand Performances, enhanced by videos created by Indian origin filmmaker Faroukh Virani, was a part of a series of outdoor events in LA last year.

The performance begins with a reminder of the laceration of the Indian subcontinent into two nation states in a matter of five weeks in 1947. The British colonial government had entrusted Cyril Radcliffe, a lawyer unfamiliar with the region, to draw its borders.

One and a half million people would be killed trying to cross the Radcliffe line and another 15 million displaced immediately after the carving of the two nations. By appointing Radcliffe to demarcate the boundaries of India and Pakistan and thereby break the deadlock between demands of the Indian National Congress and the Muslim League, Britain had attempted to project an appearance of neutrality.

Yet, the haste with which the task was accomplished suggests that neutrality was merely a mask for callousness and indifference.

The poetry, essays, and the audio-visual montage accompanying Sarwar’s reading in California Plaza sought to bear witness to the long-term consequences of Radcliffe’s disinterested cartography. Nearly 80 years later, the India-Pakistan border still crackles with tension. Wars, cross-border strikes, and conflicts continue to scratch the scabs of Partition. Civilians and soldiers die. Communities are unhomed.

As such, for Sarwar, Partition is not only a flashpoint in modern Southasian history, but also a harrowing lived experience that repeats globally, both within and across the borders of nation states. She finds echoes of Partition in the experiences of the Japanese Americans forcefully removed from their homes and placed in internment camps during the Second World War, the dying and displaced in Gaza, and in the detainment and criminalization of refugees everywhere.

WATCH VIDEO: Sehba Sarwar presents at Grand Performances in California Plaza, Los Angeles, 21 June 2024.

A performance that hinges on the refusal to forget Partition assumes that a demand or request has been made to forget the horror. Who, one may wonder, asks Partition to be forgotten? The directive to erase memory where it does not align with nationalist policies reaches survivors of Partition, mass displacement, and genocide in a variety of ways. 'Not another Partition novel' is a common response from publishers and literary circles. Some ask survivors and their children to gloss and produce knowledge or art about Partition in certain stereotypical ways to make the gashes legible to audiences who are imagined to be naïve and innocent.

Such responses suggest that people have learned all they ever could from history or that the significance of these events has been thoroughly exhausted.

The poem’s bookending her performance makes an unnamed second person “you” stand in for the authorities attempting to enforce oblivion. These are state powers and state institutions that mandate and extract — documents, fingerprints, lives. Nation states might build monuments to memorialize historical traumas, but the monuments often frame horrific events as singular occurrences.

Such framing allows everyone to pretend that the events have never happened before — nobody saw them coming — and will never happen again. State memorials consolidate a sense of nationalist pride, cementing an antagonism between an unambiguous “us” who suffered and a “them,” who inflicted the suffering without recognizing how the state itself replicates and reproduces analogous structures of oppressions.

Philosopher Theodore Adorno in his 1959 essay, “The Meaning of Working through the Past” (translated from German by Henry W. Pickford), observes that institutions often “work through the past” merely to “close the books” on it. While he acknowledges that “guilt and violence” cannot be repaid with “guilt and violence,” Adorno stresses that representatives of systems responsible for injustices have no right to insist that wounds of the past should be “forgiven and forgotten.”

Sehba Sarwar invokes the memories of her mother as well as the practices of other women — including activist Sabeen Mahmud who was assassinated in Karachi in 2015 — whose interviews play in the audio-visual montage as an antidote to state-sponsored, nationalist record keeping. Zakia Sarwar, her mother, recalls how the border between India and Pakistan seemed fluid at first. People could come and go with permits.

“Over the years, the border has hardened,” she says.

Is it possible now to imagine a map of the subcontinent without hard, jagged frame lines portioning off land? What if people who are suspicious of those from the “other” side were to trade their suspicion for border hospitality? Living in a divided world, it is easy to offer cynical responses to such questions. A borderless subcontinent, a borderless world feels like an impossibly distant dream, but Sehba Sarwar holds her work up to such a vision.

I first came across her writing and her attempts at locating herself on an imaginary map without borders in a world of hardened borders around 2017 - 2018. I was working as an editor for a now-defunct biannual Pakistan-based Southasian literary magazine, Papercuts. Born and raised in India, I wouldn’t be able to take on such a role if it weren’t remote. That Sehba Sarwar and I could meet in person in 2019, build and sustain a friendship, was made possible by our migration to the U.S.

Whereas her family had moved from what is now northern India to Pakistan during Partition, mine had moved from what is now Bangladesh (earlier East Pakistan) to India. We have both lived in the U.S. for many years but retain strong ties to our birth countries.

Meanwhile, cross-border public transportation between India and Pakistan has been intermittently put on hold throughout my lifetime, whenever political tensions boil over. There are no direct flights between India and Pakistan at the moment. The people of these nations share desires, dreams, languages, and wounds, and yet our maps of memories intersect.

In her performance, she shows clips of the ‘Beating Retreat’ ceremony of the Indian and Pakistani military at the Attari-Wagah Border. The flag lowering drill performed every sunset is suspended during conflicts, as it was from 8-20 May 2025 following the most recent eruption of violence between the two nations – so its occurrence implies something like prevailing goodwill among the neighbors.

But this dance of goodwill involves loud battle cries. The Pakistani and Indian guards move, march, and maneuver with vigor to demonstrate the strength and might of their respective nations. The handshake between representatives of the two countries at the end of the ceremony — currently suspended — functions as a spectacle for the audiences within the broader context of political hostility. She has watched the ceremony from Wagah, the Pakistan side of the border, and I from Attari on the India side.

We navigate the same borders but from different points of origin.

Partition did not merely split a piece of land. It permanently unhomed people of the region, whether or not they moved in 1947. People were exiled from a possible world that could have been defined by hospitality and kindness when they are allowed to meet rather than hostility.

Sehba Sarwar’s writing and activism insists that it is still possible to carve a future without borders, where all exiles can be home.

(*Torsa Ghosal is the author of a book of literary criticism, Out of Mind, and an experimental novella, Open Couplets. Her fiction, essays, and translation have appeared in The Kenyon Review, The Massachusetts Review, Literary Hub, Bustle, Los Angeles Review of Books, and elsewhere.)

This is a Sapan News syndicated feature available for republication with due credit.

Have you liked the news article?