Memories of childhood and curiosity, still warm, cling to my grandfather’s monolithic house in the “saffron town” of Pampore, Kashmir. How was such a structure even conceived?

What inspired the unlettered craftsmen and artisans to create, in the 70’s, a design so strikingly modernist and brutalist—with terrazzo floors, elevated verandas, and broad staircases that opened gracefully into the backyard lawns with more undulating stairs and geometrically intersecting walkways? It wasn’t vernacular.

So, what is the history behind the emergence of modernist-concrete-heavy brutalist architecture in Kashmir, and why are there no records of it? It seems, the decades of strife led to the silent erasure of our architectural memory and cultural heritage, the scale of our losses outweighing our gains.

I began looking for answers, and before long, the common denominators were staring me in the face - plain and undeniable.

Joseph Stein’s Kashmir Connection

SKICC, SKIMS, Old Srinagar Airport, Civil Secretariat, Broadway Theatre and Bakshi Stadium all shared a common design characteristic. They were concrete-heavy, brutalist, monolithic structures built between 1960 and the 1980’s. These structures rejected ornamentation and featured contrasting aesthetics from raw, exposed concrete.

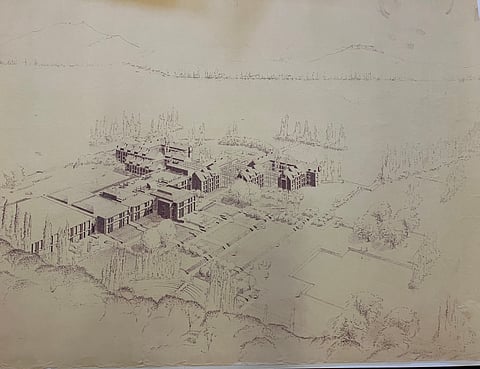

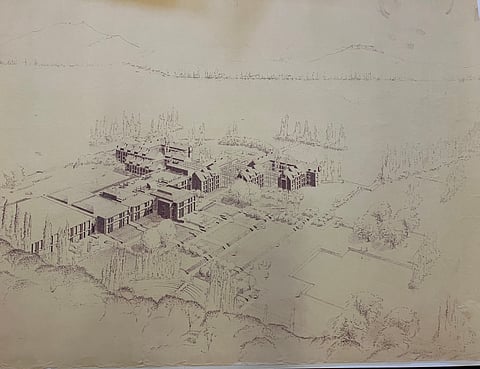

In pursuit of enriching my inner thirst for knowledge, I turned to online research, looking for architects who designed these structures. I found one name - “Joseph Allen Stein”, San Francisco, which eventually led me to rare manuscript collections at UC Berkeley, Cornell, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

After being granted a special request to examine them, I spent many weeks of meticulously scrutinising documents and handwritten notes, some of which are considered a subject matter in both modernist studies and banter politics. I discovered drawings and hand-written annotations by Joseph Allen Stein, and more importantly, the answer to the puzzle of my grandfather’s house design.

India on a Modernist Path

Post-independence, India’s leadership had ambitious goals with research in the fields of science and technology on top of its agenda. This research-oriented outlook culminated in the establishment of the IITs, conceived as pillars of scientific and technological advancement.

In the following years, India witnessed the emergence of a distinctly modernist architecture, indebted to the Bauhaus movement of the 1920s. The leadership was determined to modernise India, or as one would recall the famous words of Jawahar Lal Nehru “at the stroke of midnight hour, when the world sleeps, India will awake to life and freedom…”

Modernism became both aesthetic and ideological articulation of India’s aspirations, breaking away from a colonial past. Jawahar Lal Nehru, while visiting the US in 1952, met with educational thinkers, politicians and think-tanks. Nehru invited Jospeh Allen Stein to head the new department of Architecture and Planning at the Bengal Engineering College.

Stein, who was being wrongly accused of communism and was under investigation for his activism during McCarthy era, found a perfect moment to escape the US.

Next twenty-five years were the golden period of development in the history of modernist architecture in India. Ford Foundation, Embassy compounds of Chankayapuri, Lodi Estate a.k.a “Steinabad”, Lyuten’s Estate, and hundreds of other structures were designed and built across India by Stein. India was all set on its path to modernise. Stein, who had worked in several parts of India collaborated with local architects like Bhalla and Doshi transforming built environment across the country.

Stein and Kashmir

It wasn’t until 1968, when Stein was commissioned by the Government of India to develop a plan for a resort in Gulmarg and another on the banks of Dal Lake. In the words of Stein, “tourism was flourishing in the valley, and Kashmir needed a built-space and careful development to act as a lever for environmental conservation”.

Gulmarg resort could not bear fruits due to bureaucratic hurdles, but SKICC project took-off. While working on SKICC, in one of his diary notes, Stein claimed to have trained more than 400 Kashmiri craftsmen- carpenters and masons - to read drawings and was instrumental in introducing concrete to build heavy-monolithic spaces, thereby forever transforming the vernacular design methodology that had hitherto been strictly traditional.

My grandfather, who was once a landlord, is now in his nineties, unaware of any design philosophy that shaped his house. For him, its meaning lay in the simple comforts it offered - large rooms, open verandas, and an easy abundance of natural light coming in through multiple casement windows, located in a cross-vent pattern in each room.

The Wostas Who Mastered the Secrets

But for me, the question remained a mystery — how a meritable height in design philosophy had permeated into a section of people, who were most likely unaware of the art and design movements of the twentieth century.

So, it began - the conversation had been somewhat desultory, and then I asked the most inevitable question of all. Who designed the house? My grandfather’s response was brief.

“Wosta mason Sattar of Pampore.”

But how would a mason with no formal training design a modernist structure with such finesse? The next step in my research was to reach out to the “Wosta’s” chief mason’s family to confirm whether he had worked on any of Stein’s projects.

Sattar had died a long time ago, but as luck would have it, he was indeed involved in one of these monolithic megastructures, as confirmed by his family.

Local masons inspired by Brutalist design, which was influenced by modernist principles like those of the Bauhaus movement led to concrete-heavy residential structures, transforming built spaces in Kashmir. Although, these masons were never formally educated or went to design school, yet through their true mastery and grit, they were able to fulfil Stein’s vision for Kashmir.

Taking these drawings out of their mylar sleeves was an emotional moment for an immigrant seeking answers to questions in America about architecture and its history in Kashmir.

Fifty years after it was built, my grandfather knows the design principle that shaped his dream house.

Have you liked the news article?