There are writers who record history in thunderclaps and those who choose a slower devastation.

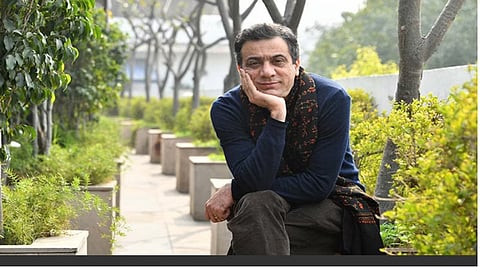

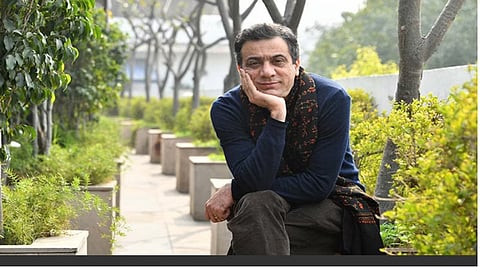

Mirza Waheed, novelist, essayist, and a journalist, belongs firmly in the latter camp. His work does not aim to shock—it exposes. Gently, deliberately, with the precision of a scalpel, he opens the wound of Kashmir and invites us to look inside.

Born and raised in Srinagar, Waheed came of age in a Kashmir that was already beginning to fray under militarisation and silence. He moved to Delhi in the 1990s to study literature at Delhi University and then to London, where he later worked at the BBC's Urdu Service.

But like so many Kashmiris of his generation, the rupture of displacement never fully left him. Though composed abroad, his fiction remains tethered to the streets and rivers of the valley he left behind.

His debut novel, The Collaborator (2011), was published by Viking/Penguin in India and Viking (UK) and later by Melville House (US). It was shortlisted for the Guardian First Book Award, longlisted for the Desmond Elliott Prize, and became a Waterstones 11 pick.

Set in a nameless border village in Kashmir, the novel centres on a teenage boy tasked with retrieving ID cards and belongings from the bodies of young men who crossed the Line of Control and never returned. These are his childhood friends. His village has been emptied by conflict, watched over by Indian soldiers, and ruled—though never truly protected—by his father, the local headman.

The Book of Gold Leaves

Waheed's prose is sparse, even at moments of horror:

"There were people dying everywhere getting massacred in every town and village, there were people being picked up and thrown into dark jails in unknown parts, there were dungeons in the city where hundreds of young men were kept in heavy chains and from where many never emerged alive, there were thousands who had disappeared leaving behind women with photographs and perennial waiting, there were multitudes of dead bodies on the roads, in hospital beds, in fresh martyrs' graveyards and scattered casually on the snow of mindless borders." (The Collaborator)

The novel is a portrait of complicity and quiet survival, of how war turns the living into record-keepers of the dead. The New York Times praised it as a "haunting debut", and The Guardian called it "a clear-eyed, unsentimental debut with real moral force."

His second novel, The Book of Gold Leaves (2014), published by Penguin India and Bloomsbury UK, shifts to a more lyrical register. Set in the early 1990s, during the peak of insurgency, it tells the love story of Roohi, a Shia schoolgirl, and Faiz, a Sunni papier-mâché artist turned reluctant militant. Their romance unfolds in the shadow of tear gas and gunfire as young men vanish into forests and never return.

Waheed writes:

"There are a thousand quiet heartbreaks, amid the loud ones that we hear about. She sometimes thinks. Some carry on quietly, over a lifetime."

(The Book of Gold Leaves)

The novel blends political unrest with deep interiority. In Kashmir, the personal is never free from the political. What begins as a love story becomes a study of loss—of place, faith, and hope. The Book of Gold Leaves was shortlisted for the 2015 DSC Prize for South Asian Literature and longlisted for the Folio Prize. The Times Literary Supplement described it as "remarkable for its lyricism and quiet restraint."

Collaboration in Ethical Sense

In 2019, Waheed's third novel, Tell Her Everything, marked a thematic shift but retained his moral urgency. Published by Westland in India and Melville House in the UK/US, the novel follows Dr. K, a successful expatriate surgeon living in London who once carried out state-ordered amputations in an unnamed Gulf country. As he writes to his estranged daughter, he seeks not absolution but understanding.

In many ways, it is a novel about collaboration—not in the political sense, but in the ethical one, about how people learn to live with what they've done and the long shadow of institutional complicity.

"My wise mother also used to say that no upbringing is worse than being brought up on a daily diet of prejudice. It darkens the soul permanently."

(Tell Her Everything)

The novel was widely acclaimed. The Jury of The Hindu Literary Prize described the book as "sensitive and complex".

The novel was widely acclaimed. The Hindu called it "a stunning, layered confession," and it won the 2019 Hindu Prize for Fiction. What Waheed does so well here is universalise the questions of Kashmir—what does it mean to obey, to remain silent, to regret too late?

Beyond his novels, Waheed is also a political essayist, with bylines in The Guardian, Granta, BBC, The New York Times, and The New Yorker. After the abrogation of Article 370 in August 2019, Waheed emerged as one of the most prominent Kashmiri voices in international media, speaking candidly about the democratic and human cost of the Indian state's actions.

In an essay for The Guardian, ‘India’s illegal power grab is turning Kashmir into a colony -Wednesday 14th August 2019’, he wrote:

“By erasing what was left of its independence the government of India, led by Narendra Modi, has chosen to unilaterally alter the future of an entire people (who have never submitted to Indian sovereignty)."

Waheed lives in London, where he writes. According to an announcement on his social media pages, his upcoming work—a much-anticipated novel, Maryam and Son—straddles the concepts of conflict and terror. The first being an interior conflict in Kashmir, where a mother’s heart grieves for a lost son in Iraq. The second, an exterior conflict, is portrayed through a brutal war that swallows the lives of sons in futile battles.

Preserving Flickering Truths

By blending personal memory with testimony, Waheed aims to preserve the fragile, flickering truths passed in whispers—the grief that doesn't fit into neat plots, the lives lived in parentheses, and the stories censored before they begin.

What distinguishes Waheed is not just his craft but his moral clarity. He doesn't romanticise suffering. He doesn't reduce Kashmir to a metaphor. Instead, he writes the stories that official histories exclude—the boy who stays silent too long, the father who cooperates to protect his son, and the doctor who looks away.

If Agha Shahid Ali mourned Kashmir as a lost paradise, Mirza Waheed writes of its unfinished war. His work does not ask us to pity or to judge but simply—to witness.

Together, these three form an accidental archive of Kashmir's long emergency.

Ali gave us the poetry of exile. Roy gave us the language of dissent. Waheed gives us the moral ledger of survival.

Ira Mathur is an Indian-born multimedia journalist based in Trinidad.

(This article has been updated with some corrrections)

Have you liked the news article?