Yamuna is the largest tributary of River Ganga. It originates from Bandarpunch glacier in Uttarkashi district of Uttarakhand and travels 1,376 kilometres (kms) before joining Ganga at Sangam (meeting point of two rivers) in Uttar Pradesh. During its course, the river also flows through the country’s capital Delhi where it turns into a ‘dead’ river.

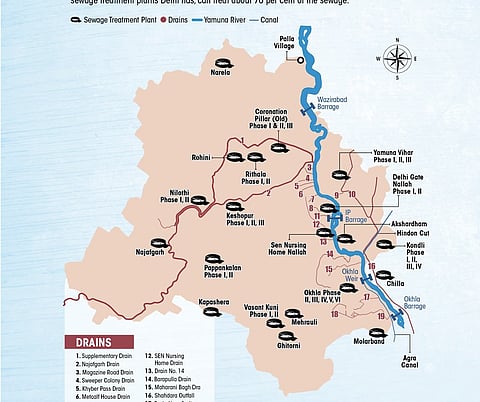

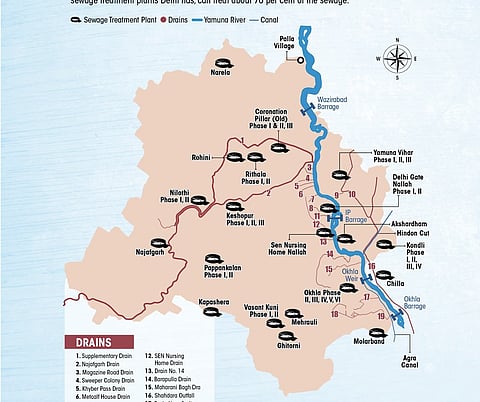

The 22-km stretch of the Yamuna in Delhi is barely two per cent of the total length of the river basin, but it contributes over 80 per cent of the pollution load in the entire river (see map: The Journey of Yamuna). There is no water in the river for virtually nine months. The city impounds the river’s water at a barrage in Wazirabad where the river enters Delhi. What flows in the river subsequently is just sewage and waste from Delhi’s 22 drains.

This is a grim testimony of Yamuna in Delhi, which has been published in a recent assessment report, Yamuna: The Agenda For Cleaning The River, which was released by New Delhi-based environmental research group Centre for Science and Environment (CSE).

The 32-page briefing document points out that at least Rs 6,857 crore have been spent in four years between 2017-2022 to clean the river, but the river is still polluted and there is no evidence that this investment is making a difference in the quality of river’s water. CSE’s report assesses key reasons for high pollution load in the river and offers an agenda for action.

“The problem of cleaning the Yamuna is not a new one; huge amounts of money have been spent over the years, plans have been initiated and carried out,” said Sunita Narain, CSE’s director general during the press briefing on May 8. “The agenda for cleaning the river is critical as a ‘dead Yamuna’ is not just a matter of shame for the city and for us—it also adds to the burden of providing clean water to Delhi as well as to the cities downstream,” she added.

“We must realise that cleaning the Yamuna will require much more than money. It will need a reworked plan which will guide us towards thinking and acting differently,” said Narain.

Sewage Treatment Plants: The Compliance Challenge

CSE’s new assessment report points out that Delhi has the capacity to treat 100 per cent of the sewage it generates. The national capital generates about 3,600 million litres daily (MLD) sewage and the installed capacity of its 37 sewage treatment plants (STPs) is 3,033 MLD, which is likely to increase to 3,652 MLD by June this year. But despite this there is no visible improvement in river quality. There is also a question mark on the credibility of data on sewage generation.

When Yamuna enters Delhi at Palla, it is alive and dissolved oxygen (DO) is close to standard prescribed. But, by the time it reaches the first monitoring station at ISBT (Inter-State Bus Terminus), it is ‘dead’, as DO level falls to zero. According to CSE, this is confirmed in the April 2025 report of Delhi Pollution Control Committee (DPCC). Aquatic species need DO to survive and thrive.

DPCC has more worrisome data to share. For instance, its 2024 records show that dissolved oxygen in midstream and downstream areas of the river was nil even during monsoon periods. Further, the biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) was 40-50 times higher than the permissible limit at these points; and the faecal coliform counts reached over two lakh in the downstream point during dry spells (see graphs: How polluted is the Yamuna).

According to CSE, despite the 37 STPs in the city, the river remains polluted because only 14 sewage treatment plants meet the standards prescribed by CPCB/DPCC, and the rest 23 STPs are not compliant. The reason being that the standards have been revised since these treatment plants were set up. The new effluent discharge standards are much more stringent for Delhi.

As per these standards, the BOD and total suspended solids (TSS) norm is now 10 milligram per litre (mg/l), which is much lower than the national standard of 30 mg/litre. This is presumably being done because of the lack of assimilative capacity in Yamuna, notes CSE in its report. This tightening of effluent standards has meant that the existing plants now need to be refurbished so that they become compliant.

Faecal Sludge Problems

Not all areas of Delhi are sewered and connected to STPs. Under the Delhi Urban Development Department’s Septage Management Regulation 2018, vehicles are registered to collect and empty septage (waste materials removed from a septic tank). By February 2024, Delhi Jal Board (DJB) had registered 160 private de-sludging vehicles and designated 86 points where this would be taken for treatment.

According to CSE’s report, on an average 1.5 million litres of septage was being collected and treated each day in Delhi. But, where this septage is being taken by private desludging vehicles is not clear, says the environmental group.

In its assessment report, CSE said that only 1 per cent of the officially generated wastewater was collected and treated as faecal sludge in February 2025. It has demanded that GPS be fixed on such vehicles to ensure septage is taken for treatment and post treatment it is recycled.

Another problem highlighted by CSE in its report is the mixing of treated sewage and untreated wastewater. The city of Delhi has 22 open stormwater channels that are supposed to carry clean water into the Yamuna (see map: Drains and STPs of Delhi). These drains receive untreated waste from either unsewered colonies or through tankers. STPs also release treated sewage into these drains. This ‘mixing’ of treated and untreated sewage must be avoided at all costs, otherwise the city will keep mixing and cleaning and wasting precious resources.

According to CSE, the treated sewage must be recycled and reused. At present, between 10 per cent and 14 per cent of the treated wastewater is reused. Each STP needs a plan not only for treatment but also for discharging its treated wastewater.

The assessment shows that the bulk of the BOD load in Yamuna is because of five drains — Najafgarh, Shahdara, Sarita Vihar, Delhi Gate and Barapulla. And of these, two major drains — Najafgarh and Shahdara — contribute 84 per cent of the pollution load. Fixing these two drains can fix pollution in Yamuna, says CSE.

Have you liked the news article?