Long before T-series mass-produced devotional albums, the mountains surrounding Vaishno Devi echoed with the reverberating local devotional songs sung to Tumbi and Sarangi melodies at the base camp and shrine. By the 1990s, these organic traditions were drowned out by commercial bhajans blaring from loudspeakers, as the sacred soundscape began to be commodified and replaced.

The devotional songs were sung in Dogri by a Gujjar Muslim family that traditionally moved between Dansal and the Trikuta hills where the shrine is nestled. Locally, these songs were called “bhaitan”.

When the Vaishno Devi Shrine Board was formed in August 1986, the family lineage that had preserved this musical tradition for generations was sidelined. Haji Ghulam Mohammad, his brother Ahmed Din and his elder brother were likely the last custodians of this dying art. Though the family continues to sing the devotional songs, their connection to Vaishno Devi and this important tale symbolising the powerful harmony of faith and the region is forgotten.

For centuries, the Vaishno Devi shrine has reflected a syncretic culture through the harmonious blending of Hindu and Muslim traditions en route the trek. While the temple's legend centers on Hindu deities like an avatar of Durga and the tantric figure Bhairon Nath, there is no Muslim figure in the core story itself.

The syncretism, however, has appeared in the lived practices surrounding the shrine.

This culture of harmony was reinforced through a Dogri folklore about Bawa Jitto (Also known as Jit Mal in many accounts), a poor peasant from village Aghar village near Katra, devoted to Vaishno Devi, who battled against feudal practices. His Dalit friends, Iso Megh and Rullo Lohar, were his main aide in this battle.

According to the legend, when Bawa Jitto's abundant grain harvest was being snatched by the local landlord Mehta Bir Singh, the goddess defended him against exploitation. This story portrays the Hindu goddess as a protector of the oppressed, and a champion of social and economic justice.

There is no mention of a Muslim in Bawa Jitto’s story that was orally transferred from one generation to another over the centuries since the medieval ages, till it was written by Prof Ram Nath Shastri and based on that script turned into a theatrical performance by Natrang. While the play ‘Bawa Jitto’ directed by Balwant Thakur has earned recognition nationally and internationally; the spirituality of Vaishno Devi shrine is woven into the story of Bawa Jitto, his anti-feudal crusade along with his friends and daughter, Bua Gauri.

My husband and editor of Kashmir Times, Prabodh Jamwal, who played a major role in researching the story of Bawa Jitto for staging the original production, notes that some parts of the story were included based on the lyrical folklore, Karkan sung by Haji Ghulam Mohammad, his family and ancestors. Haji’s family members were the traditional singers of Karkan and used to sing during the Jhiri Festival, which is a weeklong annual affair in the first week of November (Kartik Purnima).

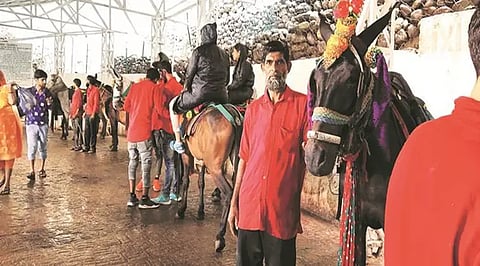

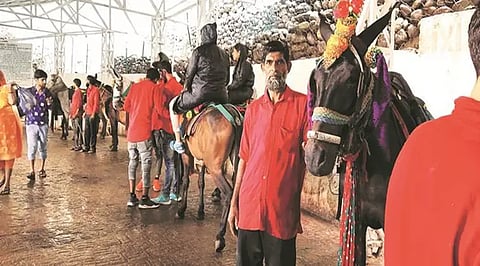

The more striking and existing example of the syncretic culture of the shrine is seen in the thousands of ponywallahs, pithuwallahs (labourers who carry the belongings of devotees) and the palanquin bearers. A teaming majority of them are Gujjar and Bakerwal Muslims from the surrounding villages and hills. Every day, they trek up and down the temple shrine carrying Hindu pilgrims, chanting with utmost fervour ‘Jai Mata Di’, matching the chorous of the devotees.

They not only guide the Hindu pilgrims, but they also offer prayers alongside them. For centuries, this tradition of mutual respect and coexistence has existed and been maintained. As per some folklore, the cave shrine itself was discovered by a Muslim. But there is no evidence to that theory.

This signifies the fluidity and inclusiveness of the shrine where shared devotion, economic interdependence, and common values create harmony that transcends formal religious boundaries. For years, the pilgrimage has demonstrated how ordinary people maintain that mutual respect, harmony and co-existence as opposed to religious exclusivity in their daily spiritual lives.

Though the tribe of local devotional singers was lost, the pilgrimage has remained as a living archive of the harmony and syncretism of the local cultures.

The recent controversy at the Shri Mata Vaishno Devi Institute of Medical Excellence exposes a stark and jarring contradiction between the shrine's historic syncretic traditions and contemporary communal politics.

Hindu right-wing groups have demanded the expulsion of 42 Muslim students, who had qualified for MBBS seats based on merit. The BJP's Leader of Opposition later presented a memorandum to the Lieutenant Governor, chairman of Shri Mata Vaishno Devi Shrine Board, demanding that all 50 seats be reserved exclusively for Hindu students, even as the institute is not a minority institution under Article 30 of the Constitution of India.

This demand stands in stark contrast to the centuries-old tradition of Muslim pony operators and palanquin bearers chanting religious slogans as they carry Hindu pilgrims to the shrine, and the devotional songs of the Muslim family.

A shrine that once symbolised interfaith harmony and mutual respect, the medical institute controversy reveals an attempt to weaponise religious identity and exclude Muslims from institutions they have every legal and moral right to access.

The claim of the Hindu Rightwing that the institute runs solely on donations from Hindu devotees has been deflated by a report that quotes official documents, which show that the Shri Mata Vaishno Devi University, of which this medical college is a part, has received Rs 121.30 crore in government grants since 2017-18.

According to the Shri Mata Vaishno Devi University website, the university was established under an Act of the J&K State Legislature in 1999 as a fully residential and technical university, the first of its kind in J&K. The land for the University’s sprawling campus, facing the shrine on an adjacent hill, was granted by the state government. Recognised by UGC under Section 2(f) & 12(B) of the UGC Act of 1956, the university receives funding from UGC.

The Medical College was added to the campus a year ago.

When taxpayer funds from all communities support an institution, the demand for religious exclusivity becomes not just discriminatory but a betrayal of the very syncretic values that made Vaishno Devi a symbol of India's pluralistic heritage.

The Muslim students studying there, and even Muslim faculty members working at the institute, embody the same spirit of shared devotion that the ponywallahs and palanquin bearers represent. Yet amidst an increasingly jarring and polarising narrative, they now face calls for their expulsion from a place the citizens taxes help fund.

In the last century, Jammu’s syncretic traditions have been under severe strain due to conflict, instability, and divisive politics that are amplified from both within and outside the state, leading to forgetfulness about Jammu’s legacy of amity. The medical college row adds yet another layer to that forgetfulness.

Yet, everything is not lost.

Amidst this distressing fraying of the social fabric, hope is renewed by the daily lived mundane examples of bonhomie. In striking contrast to the medical college controversy, what stood out this week was the heartwarming story of a Jammu-based Hindu social activist, Kuldeep Sharma, who donated land to a Muslim journalist after the latter’s house was demolished.

Just as this gesture shows that brotherhood still exists in hearts and ordinary streets, Jammu needs to rediscover its legacy and embrace it more openly.

Have you liked the news article?