On August 6, 2025, the Home Department of Jammu and Kashmir issued an extraordinary order banning 25 books under the provisions of the Bhartiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), 2023.

The justification — that these works could incite terrorism, glorify secessionism, or “distort” the Indian state’s narrative — was sweeping and vague.

The list reads like a roll call of some of the most respected minds to have written on Kashmir: Booker Prize-winner Arundhati Roy, constitutional expert A.G. Noorani, political scientist Sumantra Bose, historian Hafsa Kanjwal, journalist Anuradha Bhasin, and biographer Victoria Schofield.

Their books are taught in universities from Delhi to Harvard. Many rely on archival records, court documents, and first-hand accounts. Yet they are now officially proscribed as “a threat to national security.”

This is not the first attempt to control Kashmir’s historical and political narrative. Since the revocation of Article 370 in August 2019, New Delhi has downgraded press freedoms, tightened restrictions on civil society, and curated school curricula to align with the official line.

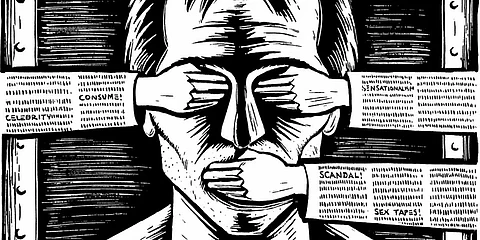

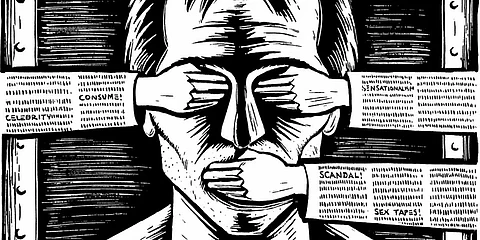

But banning scholarly and journalistic works takes control to another level. It replaces democratic debate with state-approved memory.

The BNS clauses cited in the order deal with sedition and forfeiture. Yet, in a functioning democracy, the standard for banning a book should be extremely high — requiring clear proof that it directly incites violence or causes demonstrable harm.

In Kedar Nath Singh v. State of Bihar (1962), India’s Supreme Court ruled that even advocacy of separatism is not sedition unless it incites violence. The banned books offer analysis, not agitation. Lowering the sedition threshold to cover academic interpretation or political critique risks criminalising dissent itself.

Among the banned titles are historiographical studies, ethnographic accounts, memoirs, and political analyses:

A.G. Noorani’s The Kashmir Dispute 1947–2012 — a meticulously documented legal and political history.

Hafsa Kanjwal’s Colonizing Kashmir — a study of post-1953 state-building and its impact on Kashmiri identity.

Sumantra Bose’s Contested Lands — situating Kashmir within global conflicts over territory and identity.

Anuradha Bhasin’s A Dismantled State — a journalist’s account of Kashmir after August 2019.

Arundhati Roy’s Azadi: Freedom. Fascism. Fiction — a literary critique of state repression and shrinking civil liberties.

Roy writes, “It’s a battle of those who know how to think against those who know how to hate… The hate is on the street, armed to the teeth, and protected by all the machinery of the state.”

Bhasin recalls the home minister announcing “Not a drop of blood was shed” even as officials recast Kashmir’s deafening silence as “willing acceptance.” These are precisely the ground-level narratives the ban seeks to erase.

The order claims these books could “radicalise” or “alienate” young people. In reality, few things alienate youth more than being treated as incapable of independent thought. This paternalistic assumption fosters resentment, not reconciliation.

In the digital age, banning books rarely buries ideas; it often gives them greater reach. Forbidden titles circulate online, acquire a martyr’s status, and draw more attention than they might otherwise have had.

Book bans carry a long and dark lineage. In 1933, Nazi Germany burned works by Jewish, socialist, and liberal authors to “protect” the nation. Heinrich Heine’s warning from a century earlier proved prophetic: “Where they burn books, they will ultimately burn people.”

In Turkiye, after the failed 2016 coup, thousands of books were removed from libraries, some for containing the word “Pennsylvania” — a reference to exiled cleric Fethullah Gülen. The stated aim was security; the real goal was silencing dissent.

Even in the United States, McCarthy-era pressures forced libraries to blacklist books perceived as communist. In 1953, President Eisenhower told graduates at Dartmouth: “Don’t join the book burners. Don’t think you’re going to conceal faults by concealing evidence that they ever existed.”

The lesson is clear: when states target books, they are rarely afraid of violence — they are afraid of thought.

The strength of a democracy is measured by its willingness to face uncomfortable questions, not bury them. Suppressing scholarship does not make a society safer; it makes it brittle, fearful, and detached from truth.

If those in power believe their case on Kashmir is just and moral, they should welcome scrutiny, not fear it. The real danger is not in a book — it is in the belief that only one story can be told.

Let Kashmir read. Let its people debate. That is the only way forward.

Have you liked the news article?