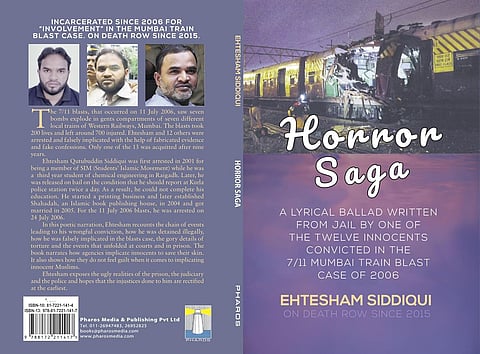

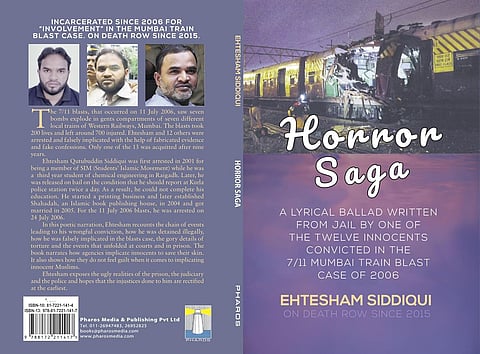

Title: Horror Saga: A Lyrical Ballad Written From Jail By One of the Twelve Innocents Convicted in the 7/11 Mumbai Train Blast Case of 2006

Author: Ehtesham Siddiqui

Publisher: Pharos Media & Publishing Pvt Ltd, New, New Delhi, India

Year Of publication: 2024

Price: Rs 250 Pages: 116

ISBN: 9788172211417

Horror Saga: A Lyrical Ballad Written From Jail By One of the Twelve Innocents Convicted in the 7/11 Mumbai Train Blast Case of 2006 by Ehtesham Siddiqui is a sustained, agonised testimony against the machinery of law, police, and media that can, in a single stroke, turn an innocent Muslim into a “terrorist” and then bury him alive in the carceral system.

Written in verse from within prison, the ballad refuses the decorum of the courtroom and the neutrality of the report. Instead, it chooses the raw, rhythmic language of a lyric as a witness’s testimony to a multitude of things. The result is a work that is at once poetic and prosecutorial, intimate and universal, personal and political.

It is a long, unbroken cry from custody, stitched together with the refrain that recurs after almost every stanza:

Because this was a setting

Hence forget about telling anybody

What had happened in the custody.

A pre-scripted tragedy

From the very beginning, Siddiqui signals that his story is not one of chance but of design. The book is framed by the foreword of Abdul Wahid Shaikh, who was acquitted after nine years and who warns the reader that the narrative ahead will be “as interesting, impactful and painful as the book is, it is also bound to shock you to the core.” (P-9)

He adds, with chilling confidence, that once you begin reading, you will not dare put the book down; and for the faint of heart, you will not dare read it at all, warning that what follows is not entertainment but exposure.

In the preface, Siddiqui states plainly that he believes he is not being punished for the blasts, but because of his strong belief in Islam. He writes that this was the sole reason why they were arrested. He contrasts their fate with that of accused in other terror‑related cases who are out on bail or acquitted, and notes that they are non‑Muslims. (P-11)

This contrast is central to his thesis. The 7/11 case, he suggests, was chosen as a site of exemplary punishment precisely because the accused were Muslims, and the state could safely project them as the “face” of terrorism without much political cost.

The lyrical ballad, he explains, is his attempt to break the silence that has been imposed on them. After conviction, many people believe they are the real culprits, but none of them know the reality. Hence, he has written this Horror Saga to tell the truth: to show what really happened during police custody, in prison, and during the trial in the Sessions Court. He wants to reveal how the prison system and the judiciary are plagued by corrupt practices, and he chooses verse as the medium through which to narrate it all. (P-12)

He writes vividly about the corruption in the judiciary, “I would have avoided writing about the corruption in the Judiciary. But my conscience does not allow me to not reveal the bitter truth. If I do not do so I might break my own principle of honesty and truthfulness, which is very dear to me. Some might become furious on reading this Horror Saga.” (P-12)

This decision is significant. The ballad form, with its repetitions, refrains, and rhythmic cadences, allows him to compress years of suffering into a compact, memorable structure, while the refrain itself becomes a kind of incantation against forgetting.

The making of a suspect

Siddiqui’s journey into the 7/11 case begins not on the day of the blasts but long before, in the everyday harassment that Muslims with any association with religious or political organisations face. He was arrested from a library, linked to SIMI, an organisation that, in the eyes of the state, is already marked as “suspicious.” That association, however tenuous, becomes the first thread that is pulled until the entire fabric of his life is unravelled.

Before the 7/11 blasts, he had already been arrested, framed, and released. But release did not mean freedom. It only meant that he had entered a new category - the “regular man” to be picked up whenever anything happened in Mumbai.

When the 7/11 blasts occurred, he was again called for “regular questioning” by the Anti Terrorism Squad (ATS). By this time, he was no longer an ordinary citizen. He was a suspect in waiting, a body already inscribed in the files of the state.

He recalls that the ATS looted Rs 25,000 he had with him and distributed it among themselves, offering a glimpse into the casual, almost ritualistic way in which the accused are stripped of dignity and resources. The fact that this looting happens before any formal charge is laid underscores both the embedded corruption and how the process of criminalisation begins long before the courtroom.

After the blasts, the nature of his detention shifts from harassment to full-blown fabrication. For four days, he is subjected to inhuman torture, after which he is formally shown as arrested in the records.

The gap between the start of torture and the official arrest is itself a kind of confession. The state knows that the violence it inflicts cannot be documented, so it hides it in that interval.

When he finally appears before the magistrate and recounts his ordeal, the magistrate tells the police to “treat him well.” Siddiqui reads this not as a rebuke but as an instruction to shift the torture from his body to that of his father. The magistrate’s words, in his eyes, become a green signal for the continuation of violence under a different name.

Torture, coercion, and the production of guilt

The ballad’s most harrowing passages are those in which Siddiqui describes the torture he and others endured in custody. The descriptions are not gratuitous; they are clinical in their precision, as if he is forcing the reader to see what the state wants to keep hidden.

He writes of being beaten, of being threatened with the rape of his sisters, of being told that his family will be destroyed if he does not sign the confession. The goal is not merely to inflict pain but to produce guilt, to make the accused accept that they are terrorists, even when they know they are not.

He notes that even after a month of torture, the police knew he was innocent, yet they decided to frame him for the train blasts. This is a crucial admission as it reveals that the case was not about evidence but about optics. The state needed Muslim faces to match the public narrative of terrorism; the actual facts were secondary.

The police, in his account, are not investigators but scriptwriters, and the accused are actors forced to sign their lines.

The ballad also exposes the role of narco‑analysis tests, which were conducted without court orders and later edited on video. The editing of the narco test footage is particularly telling. It shows that the “scientific” tools of investigation are not neutral but can be manipulated to fit a predetermined conclusion.

The refrain “Because this was a setting” thus becomes a refrain of bureaucratic cynicism where every procedure, every test, every investigation is already scripted in advance.

Siddiqui also narrates how the father of two innocent men was forced to strip and how the wife of another brother was threatened with rape so that they would confess falsely. These details illustrate how torture spills over from the accused to their kin, turning entire families into hostages of the state. The logic is simple: if you cannot break the accused, break their loved ones, and the accused will break themselves.

The “fake encounter” specialists

One of the most disturbing figures in the ballad is D.G. Vanjara, a senior police officer who tells Siddiqui that he would have killed him in a fake encounter. This admission lays bare the “fake encounter” logic.

Innocent people are sometimes eliminated because their elimination produces medals, promotions, and success stories for the force. The encounter becomes a kind of performance, staged for the media and the public, in which the line between justice and murder is erased.

In contrast to Vanjara stands the figure of ACP Vinod Bhatt, an honest ATS officer who is pressured to convict the innocents but refuses to do so. Unable to bear the weight of the pressure, he eventually commits suicide at a railway junction. His death is a powerful symbol of the moral cost of resisting a corrupt system. It also underscores the isolation of those who try to uphold integrity within institutions that have already been compromised.

Another honest ATS officer wants to send Siddiqui to jail, not because he believes him guilty, but because he knows that the police need more time to fabricate evidence. This officer is stopped, and Siddiqui is kept in custody longer so that the machinery of fabrication can complete its work. This detail reveals the extent to which the process is about producing a case that looks credible on paper, not about justice.

The judiciary as an extension of the prosecution

Siddiqui reserves some of his sharpest criticism for the judiciary.

The ballad describes a trial that is an “eyewash” and an “imposition.” The judge, in his account, has already decided that the accused are guilty and treats the presumption of innocence as a phrase for amusement. When the accused ask for defence documents, the judge consistently refuses to provide them. The phrase “Till proven guilty, accused are innocent” becomes a mockery.

Siddiqui also notes that the judge himself fills the void in the confessions and their contradictions, turning the bench into an extension of the prosecution rather than an impartial arbiter. The depositions of DCPs are forged and contradictory, yet the judge accepts them without question.

The tutoring of witnesses by the ATS is another recurring theme. Witnesses are coached to give wrong testimonies against the accused, and the judge does nothing to challenge their credibility.

On very first day he initiated the trial

Every time he was in mode of denial

Whenever we asked for defence document

Consistently he shows only dissent

Till proven guilty, accused are innocent

This phrase regularly used for amusement

Every person has religious sentiment

Whether they are police, judge or litigant

We were held guilty only on allegation

The trial was an eyewash, an imposition

And the justice, he was denying

Because this was a setting

Hence forget about telling anybody

What had happened in the custody. (P-63)

The prison economy and women in authority

The ballad also offers a grim anatomy of the prison system. Siddiqui describes how everything in prison—from food to protection—is “purchased and sold.” Those with money enjoy relative comfort, while those without it suffer.

The jailor and a goon run a racket, robbing prisoners until Siddiqui beats up the goon, after which he is transferred to another jail because the business and income have stopped. This detail illustrates the predatory nature of the prison system, which is both punitive and feeds on the vulnerability of those it incarcerates.

He also scrutinises the role of women in authority, challenging the liberal faith that more women in the police and judiciary automatically mean more justice. Swati Sathe, a woman jailor at Arthur Road jail, is described as outwardly “nice” but driven by sinister designs. She pressures the accused to turn approver in exchange for money and other rewards, revealing how the promise of leniency can be used as a tool of coercion.

Similarly, Lady Judge M. R. Bhat is portrayed as favouring the police, turning the presence of a female judge into yet another layer of complicity rather than a corrective. Siddiqui’s critique here is not against women per se but against the assumption that gender alone can redeem institutions that are structurally corrupt.

The lyrical form as resistance

What makes Horror Saga formally unusual is its choice of the lyrical ballad as a vehicle for a death‑row testimony. Ballads traditionally carry communal memory, songs of suffering, exile, and injustice, and Siddiqui harnesses that tradition to transform his personal agony into a public testimony.

The repetition of the refrain after each stanza, “Because this was a setting ……” turns the entire book into a single, looping accusation against the state.

The footnotes, which explain Urdu and colloquial terms and identify real persons, anchor the verse in documentary reality, reminding the reader that this is not fiction but a testimony given from within the carceral system. The ballad’s 200 stanzas thus function like 200 separate affidavits, each ending with the same refrain, reinforcing the unchanged core truth — this was a setting.

A testimony from the gallows

Horror Saga is not an easy book to read, and Siddiqui and Shaikh are right to warn the faint‑hearted. It is a raw, unflinching account of how an innocent Muslim engineer was turned into a “terrorist” through torture, fabrication, and a judiciary that had already decided his guilt.

At the same time, it is a formally inventive work that uses the ballad to compress years of suffering into a compact, rhythmic indictment of India’s anti-terror regime.

The fact that the Bombay High Court has now acquitted all twelve accused in the 7/11 case, citing lack of evidence and torture-tainted confessions, lends retrospective vindication to Siddiqui’s claims, even as the Supreme Court has temporarily stayed the acquittal.

In this light, Horror Saga stands not only as a personal memoir but as a crucial historical document. It is a lyrical ballad written from jail that refuses to let the public forget what really happened in custody.

Have you liked the news article?